Mother’s Daughter:

Nandana Dev Sen Translates Nabaneeta Dev Sen in Acrobat

|

The mother-daughter relationship is complicated. Freud characterized it by ambivalence, which often gives way to the daughter’s “final hostility.” My own mother defined it this way, around the time of my 18th birthday: “Two adult women cannot live in the same house at the same time.”

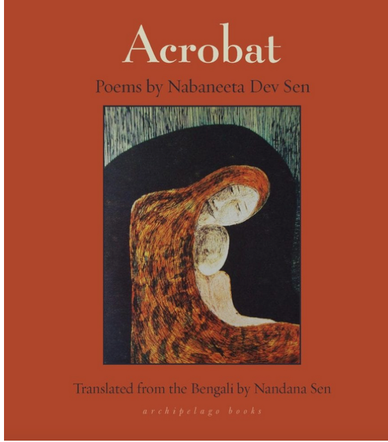

So I stand in awe of Acrobat, lyric poems by the renowned Indian writer, Nabaneeta Dev Sen (1938–2019), translated from Bengali to English by her daughter, Nandana Dev Sen. Mother and daughter collaborated on translations for over 30 years. How did they defy the Freudian dictum? How could they love other enough to craft poetry together? Maybe they were born for it, since poetry runs in the family. Nabaneeta’s parents and Nandana’s grandparents were the Bengali poets Narendra Dev (1888–1971) and Radharani Devi (1903–1989). |

The love of mother and daughter, even in the best of cases, is a paradigm for the opposing forces of attachment and separation, which are common in some measure to all relationships. Acrobat gives full voice to the emotions that arise from this opposition: joy and grief, yearning and avoidance, affection and anger. But the variations in emotion are always deft, never flagrant. The book is not an emotional rollercoaster; it is a gentle emotional landscape. Subtle feelings, which usually escape notice, slowly float into consciousness. As readers, we are, as the poem “Flute” says, “returned to the world of shadows.”

Acrobat moved me to tears on several occasions. One poem that did this was “The Lamp,” a poem about Nabaneeta’s aging mother Radharani, staying up late for poetry despite the protest of both her nurse and her child. “The Lamp” is a poem translated by a daughter, written by her mother, about her grandmother. Small wonder it warms the heart before breaking it:

I hear her, speaking softly to the nurse.

“No, no my dear,

don’t turn off the light.

Keep the lamp switched on, please.

I have just one more page left…”

Just one more page left

one more paragraph, one more sentence--

give me one more word, dear nurse,

just one more day.

The poetry in Acrobat does not need a human relationship to elicit strong emotions. The flux of nature, household objects, and even words and letters of the alphabet can love, rage, grow tired, or have an epiphany, as in the poem “All Those Crazy Blue Hills”:

And

under reddish roofs, all those white houses

suddenly grow inward, languid, weary.

Then

the clouds change their music, then

the lights change their dance, and then

all the blue hills are born again

from empty space.

In these lines, the poet experiences the world so deeply, she senses it as alive and sentient. This quality comes through in many of the poems in Acrobat. Nabaneeta Dev Sen often accomplishes what Rilke advised: that the poet be exquisitely receptive to the intelligence of all things. Nabaneeta’s achievement of this receptivity—and Nandana’s ability to capture it—was what I came to admire and enjoy most in the book.

Acrobat’s emotional resonance arises not only from the content of the poetry, but from the techniques of the translator. In her translations, Nandana Dev Sen always chooses the concrete over the abstract, the simple over the intricate, and the physical over the ethereal. In her valuable introduction to the book, Nandana explains that she wanted to capture in English the dense, succinct, pithy quality of Bengali. Indeed, many her mother’s poems are very short, but pack a punch, via the translator’s preference for active verbs and familiar, simple words. Even within longer poems, there are compact well-placed phrases that say volumes, for instance: “Time will never have the power to scorch me with its rage.”

In translating her mother’s work, Nandana also worked to meet a criterion uniquely her own: “How would Ma have written this poem in English?” Nandana also had her mother’s explicit guidance in several forms. She had Nabaneeta’s essay, “Translating Between Cultures: Translation and its Discontents,” which lays out questions to guide the translator in the areas of the spirit of the work, degree of fidelity to literal meaning, and features like rhyme, stanza breaks, and handling colloquialisms. And of course, she had years of collaboration with her mother, plus some of Nabaneeta’s own translations of her work, some of which are included in the book.

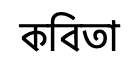

Augmenting the emotional energy of Acrobat are carefully curated and titled sections, and an elegant design and layout. These features enhance Acrobat as a book of the heart, a keepsake of family treasure. The only addition I would have liked, which might increase the book’s resonance, would be some examples of poems or stanzas in gorgeous Bengali script—shown here in the word for poetry:

Acrobat moved me to tears on several occasions. One poem that did this was “The Lamp,” a poem about Nabaneeta’s aging mother Radharani, staying up late for poetry despite the protest of both her nurse and her child. “The Lamp” is a poem translated by a daughter, written by her mother, about her grandmother. Small wonder it warms the heart before breaking it:

I hear her, speaking softly to the nurse.

“No, no my dear,

don’t turn off the light.

Keep the lamp switched on, please.

I have just one more page left…”

Just one more page left

one more paragraph, one more sentence--

give me one more word, dear nurse,

just one more day.

The poetry in Acrobat does not need a human relationship to elicit strong emotions. The flux of nature, household objects, and even words and letters of the alphabet can love, rage, grow tired, or have an epiphany, as in the poem “All Those Crazy Blue Hills”:

And

under reddish roofs, all those white houses

suddenly grow inward, languid, weary.

Then

the clouds change their music, then

the lights change their dance, and then

all the blue hills are born again

from empty space.

In these lines, the poet experiences the world so deeply, she senses it as alive and sentient. This quality comes through in many of the poems in Acrobat. Nabaneeta Dev Sen often accomplishes what Rilke advised: that the poet be exquisitely receptive to the intelligence of all things. Nabaneeta’s achievement of this receptivity—and Nandana’s ability to capture it—was what I came to admire and enjoy most in the book.

Acrobat’s emotional resonance arises not only from the content of the poetry, but from the techniques of the translator. In her translations, Nandana Dev Sen always chooses the concrete over the abstract, the simple over the intricate, and the physical over the ethereal. In her valuable introduction to the book, Nandana explains that she wanted to capture in English the dense, succinct, pithy quality of Bengali. Indeed, many her mother’s poems are very short, but pack a punch, via the translator’s preference for active verbs and familiar, simple words. Even within longer poems, there are compact well-placed phrases that say volumes, for instance: “Time will never have the power to scorch me with its rage.”

In translating her mother’s work, Nandana also worked to meet a criterion uniquely her own: “How would Ma have written this poem in English?” Nandana also had her mother’s explicit guidance in several forms. She had Nabaneeta’s essay, “Translating Between Cultures: Translation and its Discontents,” which lays out questions to guide the translator in the areas of the spirit of the work, degree of fidelity to literal meaning, and features like rhyme, stanza breaks, and handling colloquialisms. And of course, she had years of collaboration with her mother, plus some of Nabaneeta’s own translations of her work, some of which are included in the book.

Augmenting the emotional energy of Acrobat are carefully curated and titled sections, and an elegant design and layout. These features enhance Acrobat as a book of the heart, a keepsake of family treasure. The only addition I would have liked, which might increase the book’s resonance, would be some examples of poems or stanzas in gorgeous Bengali script—shown here in the word for poetry:

At the end of her introduction, Nandana Dev Sen admits that, in the time since her mother’s death, she has used the work of translation to keep her mother close. Her words touched me. My own mother was no poet, but she liked to knit and, when I was a child, knitting was one of the few things we did together. Shortly after my mother died, I found myself taking up knitting after decades away from it. Perhaps, when mother and daughter make things together, they find a way out of that Freudian “final hostility” and into love. That’s what happened to Nabaneeta and Nandana Dev Sen. We are richer for it.

— Dana Delibovi

— Dana Delibovi