|

Sisters are woefully underrepresented in poetry. When they have appeared, though, they radiate power. In Dorianne Laux’s acclaimed poem, “Two Pictures of My Sister,” the poet’s teenage younger sister laughs in the face of an abusive father and dares him to belt her again. Emily Dickinson paid tribute to her sister-in-law Susan, in “One Sister I have in our house.” Sue, as Dickinson calls her in the poem, is the hand the poet holds for comfort, the friend whose “hum, the years among, deceives the Butterfly.” Poems about sisters, though few and far between, stay with you, in the way her sister’s bruised face stayed with Laux: “a stubborn moon that trails the car all night…locked in the frame of the back window.”

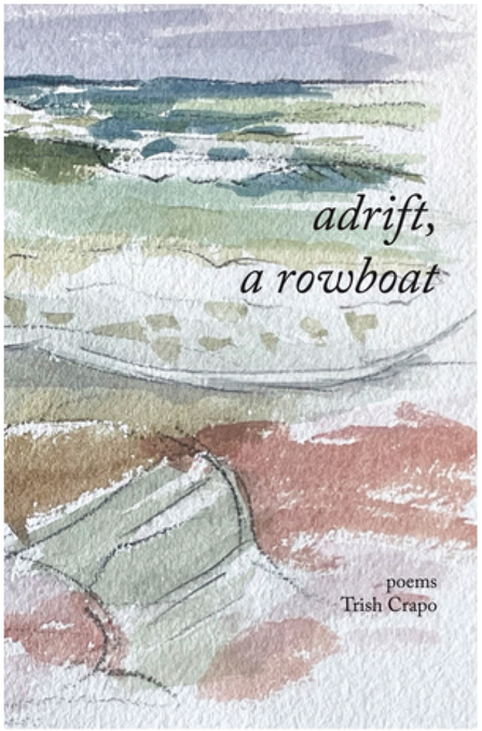

Poet Trish Crapo single-handedly boosts the representation of sisters in poetry, with her lyrical new book, adrift, a rowboat. Crapo’s book is a sequence of numbered, untitled poems devoted to her sister—another Susan—who passed away. adrift, a rowboat floats from the glittering memories of the sisters’ young lives, through the confusion of medical treatment, to death and the long, complex grief that accompanies the loss of a sibling. As such, the book is an anomaly in modern poetry: the sustained, personal tribute, belonging to the elegiac traditions of classical Rome and the British Romantics. Crapo’s poems are contemporary in their structure, but they reach to the past for depth of feeling. |

Part one of the book’s sequence of poems are childhood memories. These are among the best poems in the volume, rich with images of an American girlhood, all but gone now, where sisters played outdoors, ran from yellowjackets, and sunbathed. Crapo is very skilled at infusing an image with delicate, complex, or unusual emotions, as she does with the feeling of peace she finds with her sister, after the two ran out of the house and away from their father’s violence:

|

Wind pushed us down the sidewalk

as we hoisted the biggest umbrella, half hoping a gust would take us. Inside chaos, we spun our own calm, attached ourselves to ourselves with filaments, partly imaginary, mostly resolve. |

We are jolted out of the sisters' youth by the opening of part two—a poem in which “diagnosis is a swallowed stone” and death looms. The poems take us to cancer chemotherapy and the watchful waiting of sister-patient and sister-poet.

Embedded in this part of the sequence is a focal poem that contributes great clarity to the sequence and is, indeed, among the best in the book. The poem explains the book’s title, while creating a multi-layered metaphor for a drifting, unmoored rowboat. This poem begins with the poet asking her sister of she remembers how their father threw “the rowboat into the ocean”; how they were stranded and wanted to go home. The rowboat, adrift is all at once the lives upended by the father’s irrational violence and the unmooring of the poet’s sister through her fatal illness. At the end of a poem, another image emerges: the rowboat—if it could be wrested from the sea—as an escape from cancer and its treatment: “Oh, let’s row away from here, oh my sister…Pass me the oars.”

The three remaining parts of the book unpack the poet’s process of grief, from initial shock to a durable, accepting sadness. The very first words and the very last words of the three parts are “I rise.” At the start, in the first poem of part three, the poet’s “rise” in the morning is a searing event, full of panic and horror. At the end of the book, in the very last poem of part five, “I rise” has come to signify the poet’s determination to live with sorrow to move towards the loss of her sister rather to feel repelled by it. In between these touchstones are poems shaded with many tints of grief and memory—the full spectrum of bereavement.

While the poet achieves a great deal in these explorations of mourning, parts three and four contain a few stumbles, in the form of a handful of poems that are double-spaced, including one with also uses spatial caesuras. These poems break with the forms in the rest of the book, which are single spaced and tend to rely on indentation or stanza breaks rather than wider spacing used to provide openness and breath. The divergence of these poems from other forms disrupts of the wholeness so desirable in a poetic sequence.

adrift, a rowboat benefits greatly from Susan Crapo’s artwork. The poet’s words about her deceased sister are accompanied by this sister’s watercolors, pastels, and charcoals, on the cover and on vellum dividers. These visual images augment a quality in the book that is absent in much work today: sincerity. Trish Crapo’s volume is not one of those vain displays of craft that line the physical and virtual bookshelves these days. It is a book written in the service of love, channeling the spirit of remembrance and homage, with a humility both beautiful and rare.

— Dana Delibovi

Embedded in this part of the sequence is a focal poem that contributes great clarity to the sequence and is, indeed, among the best in the book. The poem explains the book’s title, while creating a multi-layered metaphor for a drifting, unmoored rowboat. This poem begins with the poet asking her sister of she remembers how their father threw “the rowboat into the ocean”; how they were stranded and wanted to go home. The rowboat, adrift is all at once the lives upended by the father’s irrational violence and the unmooring of the poet’s sister through her fatal illness. At the end of a poem, another image emerges: the rowboat—if it could be wrested from the sea—as an escape from cancer and its treatment: “Oh, let’s row away from here, oh my sister…Pass me the oars.”

The three remaining parts of the book unpack the poet’s process of grief, from initial shock to a durable, accepting sadness. The very first words and the very last words of the three parts are “I rise.” At the start, in the first poem of part three, the poet’s “rise” in the morning is a searing event, full of panic and horror. At the end of the book, in the very last poem of part five, “I rise” has come to signify the poet’s determination to live with sorrow to move towards the loss of her sister rather to feel repelled by it. In between these touchstones are poems shaded with many tints of grief and memory—the full spectrum of bereavement.

While the poet achieves a great deal in these explorations of mourning, parts three and four contain a few stumbles, in the form of a handful of poems that are double-spaced, including one with also uses spatial caesuras. These poems break with the forms in the rest of the book, which are single spaced and tend to rely on indentation or stanza breaks rather than wider spacing used to provide openness and breath. The divergence of these poems from other forms disrupts of the wholeness so desirable in a poetic sequence.

adrift, a rowboat benefits greatly from Susan Crapo’s artwork. The poet’s words about her deceased sister are accompanied by this sister’s watercolors, pastels, and charcoals, on the cover and on vellum dividers. These visual images augment a quality in the book that is absent in much work today: sincerity. Trish Crapo’s volume is not one of those vain displays of craft that line the physical and virtual bookshelves these days. It is a book written in the service of love, channeling the spirit of remembrance and homage, with a humility both beautiful and rare.

— Dana Delibovi