¡VIVA!

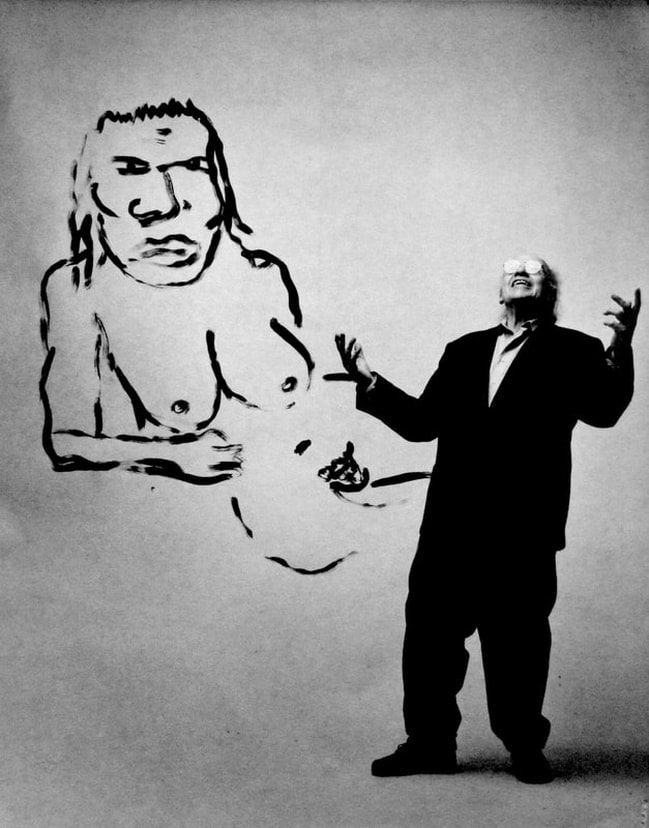

Gerald Stern: American Oracle

Dana Delibovi

Hats in the air for the poet Gerald Stern in his 96th year—a life in art, lived to the fullest.

Gerald Stern is our prophet of the particular. In his poems, stale cigars tossed from a window become the vehicles of the visionary. When a prostitute makes a gift of a faded blue iris, the withered flower must be taken home to adore. The portal to infinite creation is a backyard in New Jersey.

Gerald Stern turns 97 years old this coming February. It’s been many years since his Pittsburgh childhood, his Army days, and his first book, The Naming of the Beasts (1973). Many bleats and phonemes ago. But, as Stern would say, “how gorgeous is the distant sound of dogs?” Gorgeous indeed: Stern’s twenty books of poetry and four collections of essays overflow with lavish images, expressed in a uniquely American voice. Not the sanitized voice of the media, but the voice of the east coast, immigrant, hard-working, “hyphenated” American. A voice I love—because it is the resonant voice of my early life.

Over the course of his career, Stern has received the Wallace Stevens Award and the Ruth Lilly Prize, among many other honors. His book, This Time: New and Selected Poems, won the 1998 National Book Award for Poetry. Stern has been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship and four National Endowment for the Arts Grants. He taught at Iowa Writers Workshop, Temple University, Drew University, and New England College. The poems in his book, Lucky Life, inspired a film of the same name. Just last year, selected poems since the year 2000 were published in the marvelous volume, Blessed As We Were.

These achievements, important as they are, don’t define Stern and his legacy: the poet and his opus are larger than mere accolades. Stern speaks with an oracular conviction. God and Judaism are never far. Nor are God’s creation and the intensity of the Old Testament. But Stern is not a punitive prophet. His poems and essays are irreducibly kind. He is compassionate even when angry or sarcastic, even when is subject is tiny fly or a loutish uncle. In a word, Stern’s works are humane—a quality expressed with deft delicacy in “Greek Neighbor Home from the Hospital"--

Gerald Stern turns 97 years old this coming February. It’s been many years since his Pittsburgh childhood, his Army days, and his first book, The Naming of the Beasts (1973). Many bleats and phonemes ago. But, as Stern would say, “how gorgeous is the distant sound of dogs?” Gorgeous indeed: Stern’s twenty books of poetry and four collections of essays overflow with lavish images, expressed in a uniquely American voice. Not the sanitized voice of the media, but the voice of the east coast, immigrant, hard-working, “hyphenated” American. A voice I love—because it is the resonant voice of my early life.

Over the course of his career, Stern has received the Wallace Stevens Award and the Ruth Lilly Prize, among many other honors. His book, This Time: New and Selected Poems, won the 1998 National Book Award for Poetry. Stern has been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship and four National Endowment for the Arts Grants. He taught at Iowa Writers Workshop, Temple University, Drew University, and New England College. The poems in his book, Lucky Life, inspired a film of the same name. Just last year, selected poems since the year 2000 were published in the marvelous volume, Blessed As We Were.

These achievements, important as they are, don’t define Stern and his legacy: the poet and his opus are larger than mere accolades. Stern speaks with an oracular conviction. God and Judaism are never far. Nor are God’s creation and the intensity of the Old Testament. But Stern is not a punitive prophet. His poems and essays are irreducibly kind. He is compassionate even when angry or sarcastic, even when is subject is tiny fly or a loutish uncle. In a word, Stern’s works are humane—a quality expressed with deft delicacy in “Greek Neighbor Home from the Hospital"--

|

He has walked to the wire fence three times

to study my tomatoes and he has smelled my roses in a downward movement in which his good leg was one anchor and his cane another. |

—and with moral vehemence in "Albatross I."

|

...I would kill anyone who stuffed

a full grown frog into a mason jar and threw him from a third-floor window, the glass cutting his body, penetrating his mouth and eyes... |

Stern has never reserved his heart for the page alone. I learned that when I spoke with poets Joan Larkin and Ira Sadoff, two of Stern’s many friends and colleagues. “Jerry’s hugely generous, humane perspective is in everything,” Larkin told me. “He’ll get in an elevator, make friends, sing a song, admire someone’s hat. He is a connector of people.” Sadoff shared a story of Stern’s generosity and humor. “Jerry called me on the phone once and said I should apply for a Guggenheim. I said no, I’d already applied a few times without getting it. He said ‘Well I wrote and sent the recommendation, so you’d better apply.’ I did, and got it.”

As in life, so in art: Larkin was quick to point out to me that the prophetic “almost biblical” tone in Stern’s writing is tempered with everyday language, connection with living beings, and spontaneous emotion. Larkin captured this mix of the biblical and the conversational in her 2013 essay on Stern’s poem “Sam and Morris.” Here, Stern’s proletarian uncles, living in America, belie the anti-Semitism of Ezra Pound; Stern expresses his righteous wrath for Pound in the vernacular— “the spoken utterance” without pretense or artifice:

As in life, so in art: Larkin was quick to point out to me that the prophetic “almost biblical” tone in Stern’s writing is tempered with everyday language, connection with living beings, and spontaneous emotion. Larkin captured this mix of the biblical and the conversational in her 2013 essay on Stern’s poem “Sam and Morris.” Here, Stern’s proletarian uncles, living in America, belie the anti-Semitism of Ezra Pound; Stern expresses his righteous wrath for Pound in the vernacular— “the spoken utterance” without pretense or artifice:

|

…Of usury those

two unshaven yidden, one of them red-eyed already from whiskey, they knew nothing, they never heard of Rothschild. Their hands were huge and stiff, they hardly could eat their kreplach, Pound, you bastard! |

Stern’s vernacular is the vivid American English of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Stern’s parents, Harry and Ida, came to the United States from Ukraine and Poland, eventually settling in Pittsburgh’s Squirrel Hill neighborhood. Stern has spent his life and around the PA-NJ-NY triangle, remaining steeped in the accented patois of the region, the rich amalgam of Yiddish, Southern Italian, Greek, Polish, Spanish and many other languages. My Italian-American family in New York and Connecticut spoke with their version of this speech pattern. Even now, when we get all together, fresh-scrubbed and college educated, we quickly revert to our dialect of English. Reading Stern, I’m home.

Stern’s religion, like his language, opens the borders and pulls in the world. Stern loves God’s creation down to its humblest details. His poems revel in physical life, expressing devotion to the plants, insects, and animals of house and garden. Ira Sadoff described Stern to me as “a sensualist who identifies with animals and trees.” The paradox of Stern—Jewish monotheist, nature-loving pantheist—adds a delightful complexity to Stern’s poetry, fostering lines like “Blessed art Thou…Lord of the rhubarb.” Stern’s love of creation also extends to humble humanity, the workers, the streetwalkers, and the guys on the corner in need of a champion. “Jerry has an incredible associative imagination, “ said Sadoff, “In his best poems – innumerable— memory serves to recall his many passions, fortify his class loyalties, and show disdain for the predatory rich.”

All the virtues known to Stern’s friends are known to those who read his poetry. His list of merits comes right out of Aristotle: humane, generous, kind, wise, humorous. And, lucky for us all, prolific. Hundreds and hundreds of Stern’s poems remain in print and online at places like the Poetry Foundation. Let us read, and in this cruel and cynical age, feel his love of life.

Stern’s religion, like his language, opens the borders and pulls in the world. Stern loves God’s creation down to its humblest details. His poems revel in physical life, expressing devotion to the plants, insects, and animals of house and garden. Ira Sadoff described Stern to me as “a sensualist who identifies with animals and trees.” The paradox of Stern—Jewish monotheist, nature-loving pantheist—adds a delightful complexity to Stern’s poetry, fostering lines like “Blessed art Thou…Lord of the rhubarb.” Stern’s love of creation also extends to humble humanity, the workers, the streetwalkers, and the guys on the corner in need of a champion. “Jerry has an incredible associative imagination, “ said Sadoff, “In his best poems – innumerable— memory serves to recall his many passions, fortify his class loyalties, and show disdain for the predatory rich.”

All the virtues known to Stern’s friends are known to those who read his poetry. His list of merits comes right out of Aristotle: humane, generous, kind, wise, humorous. And, lucky for us all, prolific. Hundreds and hundreds of Stern’s poems remain in print and online at places like the Poetry Foundation. Let us read, and in this cruel and cynical age, feel his love of life.

Winter Thirst

by Gerald Stern

I grew up with bituminous in my mouth

and sulfur smelling like rotten eggs and I

first started to cough because my lungs were like cardboard;

and what we called snow was gray with black flecks

that were like glue when it came to snowballs and made

them hard and crusty, though we still ate the snow

anyhow, and as for filth, well, start with

smoke; I carried it with me I know everywhere

and someone sitting beside me in New York or Paris

would know where I came from, we would go in for dinner--

red meat loaf or brown choucroute—and he would

guess my hill, and we would talk about soot

and what a dirty neck was like and how

the white collar made a fine line;

and I told him how we pulled heavy wagons

and loaded boxcars every day from five

to one a.m. and how good it was walking

empty-handed to the No. 69 streetcar

and how I dreamed of my bath and how the water

was black and soapy then and what the void

was like and how a candle instructed me.

and sulfur smelling like rotten eggs and I

first started to cough because my lungs were like cardboard;

and what we called snow was gray with black flecks

that were like glue when it came to snowballs and made

them hard and crusty, though we still ate the snow

anyhow, and as for filth, well, start with

smoke; I carried it with me I know everywhere

and someone sitting beside me in New York or Paris

would know where I came from, we would go in for dinner--

red meat loaf or brown choucroute—and he would

guess my hill, and we would talk about soot

and what a dirty neck was like and how

the white collar made a fine line;

and I told him how we pulled heavy wagons

and loaded boxcars every day from five

to one a.m. and how good it was walking

empty-handed to the No. 69 streetcar

and how I dreamed of my bath and how the water

was black and soapy then and what the void

was like and how a candle instructed me.

Frogs

by Gerald Stern

The part that we avoided was not the heart

but what we called the pouch, for it still swelled

or seemed to and there was plenty of horror cutting

into what made the music or at least

the agency you might call it, and more than one of us

retched and as you know, that can become

contagious—think of a roomful of pouches exploding

think of the music on a summer night

with no one conducting and think of how warm it might be

and how love songs may have gotten started there.

"Winter Thirst" and "Frogs" reprinted from Blessed as We Were. Copyright (c) 2020, 2017, 2015, 2012, 2008, 2005, 2002, 2000 by Gerald Stern. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Read More

Larkin, Joan. "An American Sonnet." Field, no. 89, 2013, pp. 32-34.

Levine, Phillip. “The City of Gerald.” Field, no. 89, 2013, pp. 32-34.

Sadoff, Ira. “Gerald Stern’s Encounters With the Sublime.” Kenyon Review, vol. 36, no. 4, 2014, pp. 146-163.

Stern, Gerald. Blessed as We Were. Norton, 2020.

Stern, Gerald. Death Watch: A Meditation. Trinity University Press, 2016.

but what we called the pouch, for it still swelled

or seemed to and there was plenty of horror cutting

into what made the music or at least

the agency you might call it, and more than one of us

retched and as you know, that can become

contagious—think of a roomful of pouches exploding

think of the music on a summer night

with no one conducting and think of how warm it might be

and how love songs may have gotten started there.

"Winter Thirst" and "Frogs" reprinted from Blessed as We Were. Copyright (c) 2020, 2017, 2015, 2012, 2008, 2005, 2002, 2000 by Gerald Stern. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Read More

Larkin, Joan. "An American Sonnet." Field, no. 89, 2013, pp. 32-34.

Levine, Phillip. “The City of Gerald.” Field, no. 89, 2013, pp. 32-34.

Sadoff, Ira. “Gerald Stern’s Encounters With the Sublime.” Kenyon Review, vol. 36, no. 4, 2014, pp. 146-163.

Stern, Gerald. Blessed as We Were. Norton, 2020.

Stern, Gerald. Death Watch: A Meditation. Trinity University Press, 2016.