A Structured Emptiness

The Architecture of Poetry

by

Dana Delibovi

|

It was my first sweltering summer in New York. The summer of the serial killer Son of Sam; the summer of the devastating ’77 blackout. I liked to stand in the cool, shadowed portico of Low Library, the neoclassical centerpiece of Columbia University designed by the architects McKim, Meade, and White. I found my composure in the ionic columns, or rather, in the structured emptiness of the space between them. I absorbed the building, just as I absorbed the poetry of William Butler Yeats, my passion that year. Yeats knew how to structure emptiness, too. See and hear in “Adam’s Curse,” the line breaks, the brick-built stanzas, the start to each line with a column-like capital, and the shape Yeats gives to the emptiness of the human heart: |

|

I had a thought for no one's but your ears:

That you were beautiful, and that I strove To love you in the old high way of love; That it had all seemed happy, and yet we'd grown As weary-hearted as that hollow moon. |

There is poetry in architecture and architecture in poetry. The ancient world knew this. The philosophers and dramatic poets of classical Athens explored the dialectic of creating something new (poiesis) while recognizing eternal principles and structure (arche). In Julian-Augustan Rome, artists conceived architecture and poetry similarly, as monuments—for instance, the Ara Pacis and Catullus’s memorial to this brother, poem 101 (“And forever, brother, hail and farewell.”). In ancient China, from the time of Confucius, the culture’s poetic and philosophic sensibilities found architectural expression. One notable example, argues contemporary architect Xing Ruan, is the traditional Chinese home originating in the Zhou period, with its enclosed courtyard open to the sky.

Post-Enlightenment, theorists still connect poetry and architecture, but it’s the architects and not the poets who have been doing the heavy lifting. Architects worldwide have been unpacking the poetic elements in architecture, ever since John Ruskin published his manifesto, “The Poetry of Architecture.” A voluminous modern literature has been produced by architects about the poetic in their art, with stand outs that include Michael Graves “A Case for Figurative Architecture,” and Le Corbusier’s “Poem of the Right Angle,” As Frank Lloyd Wright said, “every great architect is—necessarily—a great poet. He must be a great original interpreter of his time, his day, his age.”

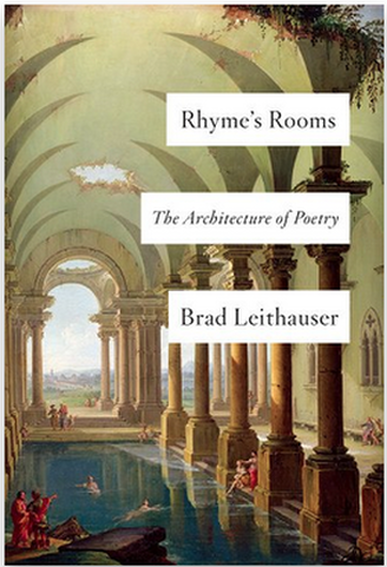

There is no comparable statement, or body of literature, from modern poets and literary critics. Apart from Gaston Bachelard’s 1958 book, The Poetics of Space—a work claimed by both architects and poets as expressing their side of the equation—poetry’s contributions to the subject have been sparse. The first modern book squarely in the poets’ camp is Brad Leithauser’s new book Rhyme’s Rooms: The Architecture of Poetry. What has been silencing the poets?

Post-Enlightenment, theorists still connect poetry and architecture, but it’s the architects and not the poets who have been doing the heavy lifting. Architects worldwide have been unpacking the poetic elements in architecture, ever since John Ruskin published his manifesto, “The Poetry of Architecture.” A voluminous modern literature has been produced by architects about the poetic in their art, with stand outs that include Michael Graves “A Case for Figurative Architecture,” and Le Corbusier’s “Poem of the Right Angle,” As Frank Lloyd Wright said, “every great architect is—necessarily—a great poet. He must be a great original interpreter of his time, his day, his age.”

There is no comparable statement, or body of literature, from modern poets and literary critics. Apart from Gaston Bachelard’s 1958 book, The Poetics of Space—a work claimed by both architects and poets as expressing their side of the equation—poetry’s contributions to the subject have been sparse. The first modern book squarely in the poets’ camp is Brad Leithauser’s new book Rhyme’s Rooms: The Architecture of Poetry. What has been silencing the poets?

|

“Whereof we cannot speak, thereof we must be silent,” are the last words of Tractatus-Logico Philosophicus by philosopher (and occasional architect) Ludwig Wittgenstein. In thrall to Wittgenstein in the 1970s, I shut up for a while. But in the ‘80s, I found myself slinking back to poetry. It all started with the poet James Merrill.

Merrill lived in a Victorian Eclectic house in Stonington, a tiny peninsula on the 5 miles of eastern Connecticut that directly faces the Atlantic Ocean. A friend and I liked to drive there, hoping to get a glimpse of Merrill. We never saw him, but we had a lot of fun looking at the architecture and drinking beer at dockside bar. Victorian Eclectic in New England is an amalgam of European styles. It piles up elements as disparate as the Greek temple, the French chateau, and the castle turret. The style is "massy" in the architect's parlance—it manages empty space with an artful farrago. Likewise, Merrill massed his poetry, piling up styles—imagism, symbolism, Cavafy’s directness, Shakespeare’s meter, and a bit of the vernacular: |

|

Dear nut

Uncrackable by nuance or debate, Eat with your fingers, wear your bloomers to bed, Under my skin stay nude… Coastline of white printless coves Already strewn with offbeat echolalia. Forbidden Salt Kiss Wardrobe Foot Cloud Peach —Name, it, my chin drips sugar… |

Maybe Merrill’s European-Victorian pile and his style-piled poems give insight into the question of the poets’ silence. Maybe poets have been tight-lipped about the connections between architecture and poetry because, as people of words, they understood where words might go. Perhaps they have held their tongues until the time was right to talk openly about the effects of European colonization on architecture and poetry—the gain and the loss, the good and the ill. The speakers of English, French, Spanish, and German, with Latin before them, colonized the world. They bent its spaces to their will. Victorian Eclectic architecture is just one of many European forms that dominate the American landscape today; so too, European poetic structures dominate our poetry. We can say this now: the colonizers trod on the spaces of others with their building footprints and their metric feet.

Poetry and architecture configure space—parcel it, distribute it, heighten it, fill it, rough it up. “Amas la arquitectura que construye en lo ausente,” wrote the poet Federico Garcia Lorca—"you love architecture that builds on what is absent.” Lorca loved poetry like that, too:

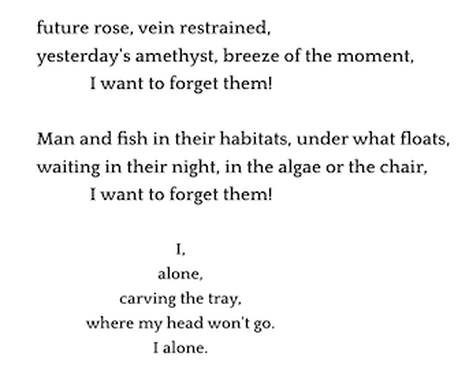

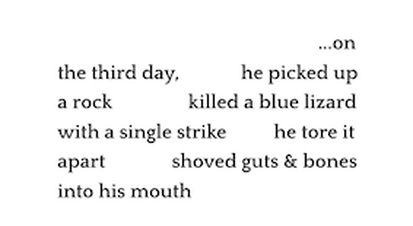

In the building on the site, in the poetry on the page, emptiness is managed visually. Buildings structure three-dimensional space with rooms, atria, hallways, domes, and caryatids. Poems structure white space with stanzas (“rooms” in Italian), line breaks, indentations, and that fine invention of Anglo-Saxon prosody and Tang Dynasty jueju—the spatial caesura, a signature of poet Eduardo Corral:

Visually, poems and buildings punctuate, stopping or eliding space. Poems have periods, commas, colons, parentheses, and Emily Dickinson’s cherished M-dash; buildings have doors, dormers, fixtures, and arabesques. Poems and buildings also play with the tension between symmetry and asymmetry, regular and irregular rhythm, pattern, and novelty: Jane Kenyon’s “Let Evening Come”; Gaudi’s “La Sagrada Familia.”

By combining these visual, physical elements, whether on the page or on the street, poets and architects can construct a limitless array of new works—endless ways to “make it new,” in Ezra Pound’s dictum. As Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno notes in his book, e.e.cummings: a Biography, Pound was a strong influence on cummings; Pound’s innovative approach to breaks, indentation, and punctuation were among the elements that inspired cummings to build poems that redefined the space on the page, as in this example where intra-word breaks and parentheses bestow depths of meaning to the haiku-like phrase: “a leaf falls, loneliness.”

By combining these visual, physical elements, whether on the page or on the street, poets and architects can construct a limitless array of new works—endless ways to “make it new,” in Ezra Pound’s dictum. As Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno notes in his book, e.e.cummings: a Biography, Pound was a strong influence on cummings; Pound’s innovative approach to breaks, indentation, and punctuation were among the elements that inspired cummings to build poems that redefined the space on the page, as in this example where intra-word breaks and parentheses bestow depths of meaning to the haiku-like phrase: “a leaf falls, loneliness.”

|

1(a

le af fa ll s) one l iness |

|

But the visual is only one aspect: Poems and building are also aural works, works of sound, works of the ear. They organize, shape, and alter sound in space. Architects think deeply about the acoustics of their buildings; they obsess about the echoes, the muffling, the effect on conversation or the clatter of dishes. Structured emptiness in architecture is experienced in the ways sound is shaped in space by the materials, configurations, and sizes of the built environment. Voices boom, for example on a walk between two massive concrete walls, but are muffled in low-ceiling, heavily furnished rooms with paneled walls. When a coin drops in a small, carpeted office, the sonic experience is quite different than when a coin drops on the parquet floor of a ballroom in 19th-century mansion.

Poetry began as vocal art, with poets—from Homer to the Ethiopian priestly poets—speaking or singing their verses. Even through poets now write their work, they remain sound artists who interrupt, elide, rhyme, meter, and otherwise shape sound in space. Sound is structured not only when a poet reads aloud, but also when a poem is “heard” in the mind of the reader. |

Every poem, like every building, has its unique and defining sound. Shakespeare gives force and conclusiveness to the final couplet of his sonnets with full rhymes and driving meter. Jean Valentine uses plosive, sibilant, and liquid consonants and short lines to create a sound that peaks then floats away, as if leaving a loud room for a quiet hallway: “pray for our friends who died/last year and the year/before and who will die this year./Let’s speak,/as the bees do.”

On occasion, poets may overtly connect the sound of verse and the sound of architecture. Gerard Manley Hopkins, whose work contains many architectural allusions, described the sound of Oxford University: “Towery city and branchy between towers; cuckoo-echoing, bell-swarmèd, lark-charmèd, rook-racked, river-rounded.” Louise Bogan yoked her language to the sound of a Roman fountain:

On occasion, poets may overtly connect the sound of verse and the sound of architecture. Gerard Manley Hopkins, whose work contains many architectural allusions, described the sound of Oxford University: “Towery city and branchy between towers; cuckoo-echoing, bell-swarmèd, lark-charmèd, rook-racked, river-rounded.” Louise Bogan yoked her language to the sound of a Roman fountain:

|

O, as with arm and hammer,

Still it is good to strive To beat out the image whole, To echo the shout and stammer When full-gushed waters, alive, Strike on the fountain's bowl After the air of summer. |

Bachelard understood that the sounds of poetry echo the sound of the built environment, especially in our homes, our emotional locus. The home delimits a region from the vastness of space, and familiar sounds in the home evoke closeness and safety (or constraint and fear, in some homes), which may find expression in poetic images. Describing a passage from Rilke, Bachelard writes: “In what silence does the stairwell resound? In this silence there are soft footsteps: the mother comes back to watch over her child, as she once did. She restores to all these confused, unreal sounds their concrete, familiar meaning. Limitless night ceases to be empty space.”

|

I want to live in a minka, the modest, traditional Japanese home. I like to imagine the sound shaped by the minka’s wooden walls and floors, in rooms that open easily one onto another with the push of a screen. There is a minka near a beach I love in Connecticut, with wide eaves and ornamental grasses that hiss in the winter wind. I looked at that house for 11 winters, and listened to the grass, with my notebook in hand.

Maybe the poet Izumi Shikibu lived in a minka in Heian Japan. Maybe she just walked past one, moving in space, straining her ear. Writing this: |

|

As I contemplate rain—dripping from the eaves, falling on irises--

on a root I've tucked in my sleeve, falls the sound of my tears. |

I live in Missouri now, and there is a minka in my town. People used to call it the Pizza Hut house, but the new owners have restored it: matte black, with subtle bas-relief of a peace sign, a stone fountain, and a yellow VW bug in the driveway. I walk by this house with my notebook, too, hoping to build a poem, subtle and stony, peaceful and black.

___________________

Acknowledgements: My gratitude to architect, poet, and all-around man of letters Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno for the many insights that shaped this essay and led me to poets whose work exemplifies the architectural. My thanks also to Bronwyn Mills, for championing the idea, to John Hess for ideas on rhythm and patterning in both architecture and poetry, and to Molly Peacock for her thoughts on the spatial caesura.

___________________

Acknowledgements: My gratitude to architect, poet, and all-around man of letters Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno for the many insights that shaped this essay and led me to poets whose work exemplifies the architectural. My thanks also to Bronwyn Mills, for championing the idea, to John Hess for ideas on rhythm and patterning in both architecture and poetry, and to Molly Peacock for her thoughts on the spatial caesura.