BECOMING

(continued)

Chris Sawyer Lauçanno

Chapter 31: I Become Lecherous

|

Since Nela, Ray's mother, had decided to stay for the summer, I created a room for myself in the adjacent roofed carport. Two large double doors blocked the entrance from the street; the other end was open, giving out onto the large overgrown backyard with its towering palm and scattering of orange and lemon trees. A high concrete wall with a top imbedded with glass shards divided our property along its entire length from the vacant lot next door; on the other side was the exterior wall of the house with two large steel barred windows that looked into the living room.

|

I didn't mind being relegated to an open-air room. In fact, I was delighted to live outside. It was stiflingly hot that summer, and while no strong breeze blew, the portico was definitely the coolest spot, particularly at night. For a bed, I had a multi-colored Juchitán hammock. I propped a piece of plywood on top of a couple of empty dynamite boxes and created a desk. I can't recall what I used for a dresser. Perhaps I kept my clothes inside the house.

Although the last six weeks of the summer were hardly as exciting as the first couple of months had been, I was neither bored nor unhappy. I quickly assumed the role of errand boy, doing most of the marketing, and after Ray returned a couple of weeks after I had re-arrived, I made frequent runs to the liquor store to buy bottles of tequila and cases of beer. The consequence of being the household helper was that by the end of the summer, I knew practically every street in Piedras and was on nodding terms with a great many of its residents.

I also read and wrote a lot that summer, but I have no recollection of what absorbed me in literature save Conrad's Nostromo. I identified with the Goulds and with the silver mine, with being a foreigner imbued with the local culture. I'm sure I missed the larger theme of the book, so taken was I by the silver mining concession. I can recall only dimly what I was writing but I know it had something to do with La Fronteriza.

Between household tasks and my creative pursuits, I had little time nor inclination to make real friends, but I did have a number of youthful acquaintances. Across the street lived two brothers about my age who decided I should learn how to play soccer. Soon I was playing midfield with them in the late afternoon after the sun had crested. I took to soccer right away and, apparently, I was a fast learner because the brothers continually told me how I had far exceeded their expectations. Curiously, I don't remember spending much time with the brothers off the playing field. After a practice or game, we’d disappear into our respective houses, meeting up again only on the pitch.

Next door lived a family with four kids. I have forgotten the names of the little ones but Sonia, the oldest, is quite memorable. She was about 14 or 15, with long shiny black hair framing an angular face with high cheekbones, gigantic brown eyes, dark skinned, long legs, slender shoulders, and excitingly full breasts. She seemed rather oblivious of her beauty; at least I can never remember her wearing makeup or obviously dressing to please. She often wore one of two dresses, both faded, one brown, one pink, both low-cut. This provided me with the continual challenge of engaging her in some activity where she was forced to bend down, thus offering me a thrilling, albeit fleeting glimpse of her breasts. To my continual delight she frequently tossed a beach ball back and forth to her little brothers, and I quickly discovered this game offered her the best chance to reveal her breasts to me.

As soon as I would hear the slap of the ball on the pavement outside their house, I would abandon whatever I was doing and rush out the front door to join her and her siblings. If she was wearing one of her white blouses or her modest blue dress with a high collar, I would simply walk by after exchanging polite greetings. But if she had on either the scooped-top brown or pink dress, I would join in on the game, making sure to position myself opposite her. I would then expertly toss the ball in her direction, careful each time that the bounce was a bit slight so that she would have to bend over to retrieve the ball. Usually, to my chagrin, she tired of playing after a few minutes, leaving me agitated and unfulfilled. Occasionally, however, she would sit on the step in front of her doorway afterwards, allowing me to engage her in conversation. All the time of course, I sought to peek down her blouse or dress. She never let on that she was aware of my lecherousness, but I think now that it would have been difficult for her not to have noticed.

Sonia's life was not very happy. She spent most of her time caring for her brothers, having even dropped out of school so that she could look after them year round. Her mother worked at the fruit market down the street and her father was a truck driver. She told me one day that she liked it when her father was gone, as he frequently was, because when he was home, he was always drunk and abusive. She didn't really need to tell me this. Since I slept outside, I was privy to the evening sounds. All too often I would be jolted awake in the middle of the night by her dad’s drunken tirades. In the darkness I would lie in my hammock listening to him shouting at his wife or daughter or both—the little boys seemed exempt from his rages. I rarely heard rejoinders from either of his two victims. Often a few moments of pure silence would intervene between outbursts, and the night would again fill with the buzzes of insects or the chirps of crickets, and perhaps the woosh and hum of a passing car or the distant barking of a dog. Then the bellowing would return followed by dull thuds of fists against flesh. And then abruptly, as if a sound curtain had descended on the house next door, everything would grow quiet again save for the armies of crickets blithely singing their way toward dawn.

***

Chapter 32: I become a Resident of El Paso

My summer idyll ended when school started at the beginning of September. I wasn't pleased about it, but there wasn't much I could do since I was only entering eighth grade and could hardly persuade my mother to let me quit. I think that was maybe the only time in my life when I did not want to be a student. Perhaps it had something to do with my not having much liked the school during the month or so I'd attended the spring before, but I think the driving force behind my scholastic disinterest was that I had discovered that life was vastly more delightful and entertaining and complex than homework or teachers or P.E. class. Besides, I reasoned, I could read and write at adult levels and solve practical math problems. Why then, did I need to spend my days confined in a classroom when the world was such a fabulous teacher? I'm sure I never uttered a word of protestation, however, since I was also wise enough to know that it would be of absolutely no use. Instead, I pedaled off each morning on my trusty one-speed bicycle, across the bridge, through the small center of Eagle Pass, and past the new split-level developments where the Junior High was located. It took about a half-hour each way, but I didn't mind the ride; it gave me thinking time and was far preferable to the classroom.

I'm not surprised given my disinterest in school, that I remember absolutely nothing about the Junior High: not the name of a single teacher or classmate, nor what classes I took, nor any experiences whatsoever. I vaguely recall that I became acquainted with some kid named José or Jaime or something, and that I went over to his house after school a couple of times, and that he had a pet iguana and a cache of Playboys. I found the magazines more diverting than the iguana, though I did like the way the little creature would catch flies with his tongue.

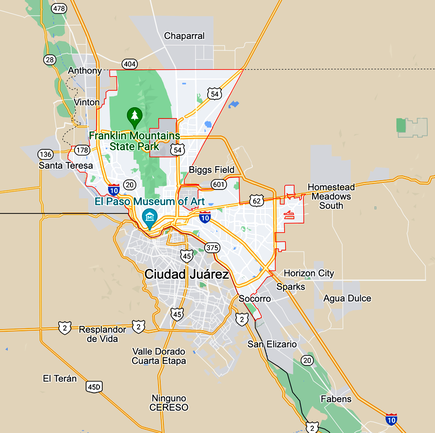

In late October of 1963, Ray announced rather suddenly that we were moving again, this time to El Paso, a town where he had lived as a kid and where he had a group of relatives ready to take us in. The mine, though rich in silver, was too remote to make it easy to get the tons of ore out without a sizable investment, and by that fall the money had dried up, and his Mexico City friends had not come through with promises to provide more. I, naturally, was aware that things had gotten precarious, but I was, nonetheless, felled by the news. I figured that somehow, some way money would materialize to save the mine and us. But I quickly learned that Horatio Alger's world was a cruel fiction, a hoax. I had, probably not so coincidentally, read about a half-dozen of his little fantasy tracts that fall and identified with Frank, Joe, Harry, Bob, Andy and Herbert and was sure that our hard work would yield results in the form of some rich man willing to part with his money for a worthy cause.

Nela had by then already moved to El Paso to act as an advance guard to pave the way for our coming. And so one balmy day in early November we packed up the trailer and set off for the other side of Texas. Neither the trip nor our arrival was particularly momentous. About all I remember of it is holding Cesar on my lap most of the journey.

Upon arrival we moved temporarily into a very cheap, one-bedroom, cockroach-infested apartment that Nela had found for us. Ray went to work the day after our arrival as a proofreader (his fall-back trade) at the El Paso Times. My mother began looking for work, as Ray's mother had generously offered to look after Cesar. I was enrolled in El Paso High School, as the eighth grade was amalgamated into the upper school.

I was not sad about leaving Eagle Pass Junior High, but I was hardly overjoyed at having to break into a new school. Fortunately, I made friends almost immediately with a Chinese kid who lived up the street named Lawton Wong; within a week, unlike in Eagle Pass where I had been virtually friendless, I found myself, thanks to Lawton, part of a small social circle.

I didn't like El Paso much. The wind blew a lot; the new apartment—we moved just a month after our arrival into the somewhat renovated basement of Ray’s Aunt Josefina's house—was cramped and dark and I had to share a room with my baby brother; my mother and Ray were unhappy; and the school seemed large and bewildering. I couldn't, in fact, fathom the setup at all. Ninety percent or so of the students were Mexican-American but not one teacher on the whole faculty was. In addition, speaking Spanish, the lingua franca of the student body, was prohibited. I suppose this latter rule was imposed because of the Anglo makeup of the faculty, but it was claimed that the reason was so that students could get used to speaking English. Corporal punishment—swats on the butt with a wooden paddle, which I endured occasionally —was the major corrective mode for misbehaving boys, misbehavior being very loosely defined: not doing homework, talking in class, speaking the outlawed Spanish language. What bothered me the most, however, was simply that the flow of life, after my exhilarating time in Mexico, seemed totally boring.

There was a dreadful excitement a few weeks after I started school there. One day around noon, the principal announced over the loudspeaker that the governor of Texas and the President of the United States—in that order—had been shot in Dallas. School was dismissed. I walked home with Lawton, Guillermo and Jesús and talked about what was going to happen now to the country. We were all in a weird state of shock, our belief in the status quo shattered, our innocence shot down as surely as was Kennedy. Over the next few days, I was riveted to the T.V., watching Oswald get shot and the president’s funeral, feeling in my bones the sense of despair that seemed to grip the entire country.

I had wanted to go back to Mexico from the moment I had left; the assassination only amped up this feeling of estrangement from my own country. I used Kennedy's murder as ammunition to pressure Ray and my mom to get out of the US again. My naïve point was skewed but my emotions weren't. Instead, they persuaded my grandparents to send money for a bus ticket for me to go to Denver over Christmas vacation.

I was glad to get out of Texas for a couple of weeks and eager to see my grandparents and uncle and his family which now included a new cousin, born after we had gone to Mexico. Curiously, I remember only one day of the entire visit, probably because it was a day that changed everybody's life, at least for a while. Over dinner at my uncle’s house on a Sunday afternoon I garrulously held forth on my adventures in the wild and in Mexico City and explained in minute detail that while Ray was a genius at discovering rich ore-laden mines, he needed investors to transform his finds into reality. My aunt quickly tuned out of the conversation but my uncle listened in rapt attention. He grilled me on the sort of capital needed, the laws, the prospects, on Ray’s ingenuity. By the evening his eyes were dancing.

The next day he had Ray on the phone. My uncle, as it turned out, had been investing in the stock market and had managed to put away a small but substantial nest egg. A friend named Smitty had done the same. Most importantly, both were looking for a new venture, and in my uncle's case, a new adventure. As he had now to support a family, he had become a telephone man and that was not his idea of a life.

Things happened rapidly after that. By the time the Greyhound had pulled into the station in El Paso on my birthday, the 4th of January, my uncle, Smitty and Ray had formed a partnership to exploit the latent load that lurked, at least according to me, under just about every surface of Mexican soil. I don't recall getting much credit, if any at all, for saving Ray from the drudgery of working at the paper, and us from Texas, but it didn't matter a lot to me. Like one of Alger's fine young lads, I took my reward from the fact that something good had happened, and that more good was sure to follow, and that I, in addition to the other members of the family, were going to cash in on it.

In the meantime, I got assigned to help with preparations for the trip that Uncle John and Ray were planning to make in April. Ray acquired a beat up 1954 red Ford pickup, along with a Motors 1954 repair manual, and I was assigned the task of making small repairs on the truck. I quickly made a mess of things, despite the manual, and was instead given the job of building a large locked box to carry goods in the back of the truck. I leapt into this task with zeal, much preferring carpentry over mechanics, and produced in a couple of days a sturdy plywood and pine container, five feet long and three feet wide, complete with an oversized brass padlock assembly, whose hasp extended about one-quarter of the way down the side of the box.

In the evenings I'd sit with Ray and go over the Mexican map with him, plotting the course he and my uncle would take. Ray had decided that as there wasn't sufficient cash to revitalize La Fronteriza, a new mine had to be discovered. The area of interest included most of northern Mexico. I was dying to go with them but knew there would be no way I would be allowed to skip school for a couple of months. Uncle John came toward the end of March and on the first of April the two prospectors set off. I think I believed, up to the moment they actually drove down the street, that some last-minute benediction would be bestowed on me that would put me in the seat between them, but alas it was not to be.

***

Chapter 34: I Become an Accompanist

Perhaps because it was a requirement, I joined the school choir at the beginning of 1964. Despite my musical heritage, I was no singer; but I tried my best, and the director, a tall gangly red-haired fellow named Morrison, was fairly kind: one lousy voice in the alto section, I suppose he reasoned, wouldn't ruin the show. But then, a few weeks after Ray and my uncle had headed off on their grand excursion, the girl who usually played the piano was out sick. Morrison asked if anyone in the chorus could take her place. No one responded. Then, after waiting several seconds for someone else to volunteer, I feebly raised my hand. Morrison eyed me rather skeptically but motioned for me to come forward.

He thrust some sheet music into my hands, then asked, “Can you play this?” It was “Babes in Toyland.”

“I think so,” I said.

“Well, play it then. Class, let Chris run through this. If he can do it, we will continue; if not I'll play it, and Chris, you can rejoin the choir.”

I glanced at the score. It didn't seem difficult, but I hadn't touched the piano in almost a year. I seated myself, arranged the music, stared at the keyboard for a moment, allowed the anxiety to course through my veins, then exit into the still classroom air. I played the first few measures rather slowly, almost tentatively, but by the fifth or sixth bar, everything radically changed. The classroom faded, Morrison disappeared, I picked up the tempo, and it was just me and the piano. And even though I hit a wrong note or two, and even though the music was fairly sappy, I was almost instantly transported beyond myself. My normal brain disengaged from the procedure, was replaced by some unconscious, unbidden force that moved my fingers across the keys, that produced from the back of the instrument glorious sounds. I finished the piece, rested my hands on my lap, and reemerged into reality. No one spoke for a few seconds. Then suddenly behind me I heard applause. Out of the corner of my eye I saw Morrison. He was beaming.

“Very well done,” he said. His ginger eyebrows were arched, as if my performance had taken him by surprise. “Let's do it for real. A little slower, however.”

After class Morrison told me he wished I could be the regular accompanist but that he had committed to Teresa for the year. I told him that was fine, that I really didn't want the job anyway. I went to get my things, but he called me back and began to grill me about my musical education. I gave him an abbreviated version.

“But why aren't you taking lessons now?” he queried, his green eyes staring intently at mine.

“I don't have a piano anymore.”

“Are you going to get one? You've got to get one!” He was wrinkling his forehead and he looked angry.

“I don't think so,” I said. We don't have much money right now.”

“You could rent one. They're not expensive to rent. But you have got to study again.” He looked over at the piano. I was pleased he wasn’t staring at me, at least for a few moments.

“I don't really want to take lessons anymore. It's too much of a hassle”.

He scowled, then burst out, “You're lying!”

I didn't know what to say.

He gazed hard at me, then said, gently now, “Chris, you can practice here every day after 4:00 o'clock if you want, I'll try to coach you, but frankly your talent requires a teacher far more accomplished than I. Do you have music?”

“No,” I said. “I left it in Denver.”

“What do you want to play? I'll get it for you.”

“No, really, that's OK,” I protested. “I don't think I can do this. I mean. Oh, I don't know. I mean….”

He cut me off. “What do you want to play?” he asked again. Now he looked as if he were about to cry, but his voice was resolute.

“How about Satie or Scriabin?” I looked at the floor, then mumbled, “I was working on both when I quit. The Gymnopédies and Scriabin's first sonata. The one in F minor.”

He chuckled, and his face, which had been so drawn, now widened. “You have eccentric tastes, young man. But consider it done. Be here tomorrow at 4:00 o'clock sharp. I’ll probably have to order the scores but I have plenty of music you can begin with. Chopin? Beethoven?"

“Thank you. Either is fine. But do you have Debussy?”

“Debussy it is until the Satie and Scriabin come through.”

I walked home by myself. I wanted to feel happy, but I didn't. I wanted to think that Morrison was handing me an opportunity, and I knew I should be grateful for it, but instead I was in a state of near panic, partly because I couldn't immediately grasp why I was feeling so ambivalent. The half hour at the piano that day, despite the repertoire, had been highly exhilarating. I had, without a doubt, loved it, and I wanted more than anything to continue to play but I was completely afraid of commencing again. I walked along, not really seeing anything or anybody. My hands were sweating; I felt feverish. Some kid I knew from English class hailed me and it took me a moment or so even to respond, so deep was I in my neurotic muddle.

Then, in San Jacinto Plaza, while looking at the alligators in their fenced enclosure, it hit me. My life, I said to myself, wasn't headed in that direction. We were going back to Mexico and Mexico was not equated with pianos. And at the moment we were poor, and I knew that playing just a bit each day on the piano in the music room was not enough either to help me improve or to satisfy me. I couldn't take up Morrison's offer. I couldn't start again and then stop in a few months.

Playing music had been like being on heroin. The high, while doing it regularly was immense, but the withdrawal had been awful. For a long while after I'd quit, every time I'd pass a piano, even in a public place, I would often have a powerful urge to run my fingers over the keyboard. I once found myself in the crowded Focolare cocktail bar in Mexico City, between sets, inching my way toward the instrument, fingers already splayed, my heart beating wildly. Only an extraordinary effort of will had allowed my sense of decorum to prevail over my need. That had been months ago, and until today, I had prided myself on being cured. But I had become intoxicated again, and I feared the outcome of repetitive doses of the piano drug, then addiction, then having to kick again.

All this, while probably not so carefully articulated, had been rattling around in my head as I circuitously made my way home. It was almost dark, the streetlamps on, when I finally started up the hill. Then about halfway up, the apartment visible, I suddenly turned on my heels and began running. I covered the mile or so between the house and the school in short order. Some lights were on in the building, but the main door was locked. I ran around to the side, found a door open, and quietly entered.

My fingers were twitching with anticipation of getting them on the piano keys again. Rhythms and melodies pounded in my forehead as I rapidly ascended the stairs and bounded down the corridor only to come up against the music room's locked door. I knocked on it, though I knew of course, that no one would answer my plea for entrance. Finally, in resignation I slid to the floor, opened my satchel, took out some notepaper, and wrote in haste a letter to Morrison. It said something to the effect that I thanked him for his interest in me, but unfortunately, I would not be able to accept his kindness since I had to be home immediately every day after school to look after my little brother. I didn't reread the note, just slipped it under the door. Then turning away, I slowly walked down the dark corridor, descended the stairs and slid out the door and away from the piano and Satie and Scriabin and another life, and made my way tonelessly into the night.

***

NOTA BENE: The inaugural issue of Wet Cement Magazine has new work by the author. Night Suite, his newest book of poems, will be out later this year from Talisman House.

Although the last six weeks of the summer were hardly as exciting as the first couple of months had been, I was neither bored nor unhappy. I quickly assumed the role of errand boy, doing most of the marketing, and after Ray returned a couple of weeks after I had re-arrived, I made frequent runs to the liquor store to buy bottles of tequila and cases of beer. The consequence of being the household helper was that by the end of the summer, I knew practically every street in Piedras and was on nodding terms with a great many of its residents.

I also read and wrote a lot that summer, but I have no recollection of what absorbed me in literature save Conrad's Nostromo. I identified with the Goulds and with the silver mine, with being a foreigner imbued with the local culture. I'm sure I missed the larger theme of the book, so taken was I by the silver mining concession. I can recall only dimly what I was writing but I know it had something to do with La Fronteriza.

Between household tasks and my creative pursuits, I had little time nor inclination to make real friends, but I did have a number of youthful acquaintances. Across the street lived two brothers about my age who decided I should learn how to play soccer. Soon I was playing midfield with them in the late afternoon after the sun had crested. I took to soccer right away and, apparently, I was a fast learner because the brothers continually told me how I had far exceeded their expectations. Curiously, I don't remember spending much time with the brothers off the playing field. After a practice or game, we’d disappear into our respective houses, meeting up again only on the pitch.

Next door lived a family with four kids. I have forgotten the names of the little ones but Sonia, the oldest, is quite memorable. She was about 14 or 15, with long shiny black hair framing an angular face with high cheekbones, gigantic brown eyes, dark skinned, long legs, slender shoulders, and excitingly full breasts. She seemed rather oblivious of her beauty; at least I can never remember her wearing makeup or obviously dressing to please. She often wore one of two dresses, both faded, one brown, one pink, both low-cut. This provided me with the continual challenge of engaging her in some activity where she was forced to bend down, thus offering me a thrilling, albeit fleeting glimpse of her breasts. To my continual delight she frequently tossed a beach ball back and forth to her little brothers, and I quickly discovered this game offered her the best chance to reveal her breasts to me.

As soon as I would hear the slap of the ball on the pavement outside their house, I would abandon whatever I was doing and rush out the front door to join her and her siblings. If she was wearing one of her white blouses or her modest blue dress with a high collar, I would simply walk by after exchanging polite greetings. But if she had on either the scooped-top brown or pink dress, I would join in on the game, making sure to position myself opposite her. I would then expertly toss the ball in her direction, careful each time that the bounce was a bit slight so that she would have to bend over to retrieve the ball. Usually, to my chagrin, she tired of playing after a few minutes, leaving me agitated and unfulfilled. Occasionally, however, she would sit on the step in front of her doorway afterwards, allowing me to engage her in conversation. All the time of course, I sought to peek down her blouse or dress. She never let on that she was aware of my lecherousness, but I think now that it would have been difficult for her not to have noticed.

Sonia's life was not very happy. She spent most of her time caring for her brothers, having even dropped out of school so that she could look after them year round. Her mother worked at the fruit market down the street and her father was a truck driver. She told me one day that she liked it when her father was gone, as he frequently was, because when he was home, he was always drunk and abusive. She didn't really need to tell me this. Since I slept outside, I was privy to the evening sounds. All too often I would be jolted awake in the middle of the night by her dad’s drunken tirades. In the darkness I would lie in my hammock listening to him shouting at his wife or daughter or both—the little boys seemed exempt from his rages. I rarely heard rejoinders from either of his two victims. Often a few moments of pure silence would intervene between outbursts, and the night would again fill with the buzzes of insects or the chirps of crickets, and perhaps the woosh and hum of a passing car or the distant barking of a dog. Then the bellowing would return followed by dull thuds of fists against flesh. And then abruptly, as if a sound curtain had descended on the house next door, everything would grow quiet again save for the armies of crickets blithely singing their way toward dawn.

***

Chapter 32: I become a Resident of El Paso

My summer idyll ended when school started at the beginning of September. I wasn't pleased about it, but there wasn't much I could do since I was only entering eighth grade and could hardly persuade my mother to let me quit. I think that was maybe the only time in my life when I did not want to be a student. Perhaps it had something to do with my not having much liked the school during the month or so I'd attended the spring before, but I think the driving force behind my scholastic disinterest was that I had discovered that life was vastly more delightful and entertaining and complex than homework or teachers or P.E. class. Besides, I reasoned, I could read and write at adult levels and solve practical math problems. Why then, did I need to spend my days confined in a classroom when the world was such a fabulous teacher? I'm sure I never uttered a word of protestation, however, since I was also wise enough to know that it would be of absolutely no use. Instead, I pedaled off each morning on my trusty one-speed bicycle, across the bridge, through the small center of Eagle Pass, and past the new split-level developments where the Junior High was located. It took about a half-hour each way, but I didn't mind the ride; it gave me thinking time and was far preferable to the classroom.

I'm not surprised given my disinterest in school, that I remember absolutely nothing about the Junior High: not the name of a single teacher or classmate, nor what classes I took, nor any experiences whatsoever. I vaguely recall that I became acquainted with some kid named José or Jaime or something, and that I went over to his house after school a couple of times, and that he had a pet iguana and a cache of Playboys. I found the magazines more diverting than the iguana, though I did like the way the little creature would catch flies with his tongue.

In late October of 1963, Ray announced rather suddenly that we were moving again, this time to El Paso, a town where he had lived as a kid and where he had a group of relatives ready to take us in. The mine, though rich in silver, was too remote to make it easy to get the tons of ore out without a sizable investment, and by that fall the money had dried up, and his Mexico City friends had not come through with promises to provide more. I, naturally, was aware that things had gotten precarious, but I was, nonetheless, felled by the news. I figured that somehow, some way money would materialize to save the mine and us. But I quickly learned that Horatio Alger's world was a cruel fiction, a hoax. I had, probably not so coincidentally, read about a half-dozen of his little fantasy tracts that fall and identified with Frank, Joe, Harry, Bob, Andy and Herbert and was sure that our hard work would yield results in the form of some rich man willing to part with his money for a worthy cause.

Nela had by then already moved to El Paso to act as an advance guard to pave the way for our coming. And so one balmy day in early November we packed up the trailer and set off for the other side of Texas. Neither the trip nor our arrival was particularly momentous. About all I remember of it is holding Cesar on my lap most of the journey.

Upon arrival we moved temporarily into a very cheap, one-bedroom, cockroach-infested apartment that Nela had found for us. Ray went to work the day after our arrival as a proofreader (his fall-back trade) at the El Paso Times. My mother began looking for work, as Ray's mother had generously offered to look after Cesar. I was enrolled in El Paso High School, as the eighth grade was amalgamated into the upper school.

I was not sad about leaving Eagle Pass Junior High, but I was hardly overjoyed at having to break into a new school. Fortunately, I made friends almost immediately with a Chinese kid who lived up the street named Lawton Wong; within a week, unlike in Eagle Pass where I had been virtually friendless, I found myself, thanks to Lawton, part of a small social circle.

I didn't like El Paso much. The wind blew a lot; the new apartment—we moved just a month after our arrival into the somewhat renovated basement of Ray’s Aunt Josefina's house—was cramped and dark and I had to share a room with my baby brother; my mother and Ray were unhappy; and the school seemed large and bewildering. I couldn't, in fact, fathom the setup at all. Ninety percent or so of the students were Mexican-American but not one teacher on the whole faculty was. In addition, speaking Spanish, the lingua franca of the student body, was prohibited. I suppose this latter rule was imposed because of the Anglo makeup of the faculty, but it was claimed that the reason was so that students could get used to speaking English. Corporal punishment—swats on the butt with a wooden paddle, which I endured occasionally —was the major corrective mode for misbehaving boys, misbehavior being very loosely defined: not doing homework, talking in class, speaking the outlawed Spanish language. What bothered me the most, however, was simply that the flow of life, after my exhilarating time in Mexico, seemed totally boring.

There was a dreadful excitement a few weeks after I started school there. One day around noon, the principal announced over the loudspeaker that the governor of Texas and the President of the United States—in that order—had been shot in Dallas. School was dismissed. I walked home with Lawton, Guillermo and Jesús and talked about what was going to happen now to the country. We were all in a weird state of shock, our belief in the status quo shattered, our innocence shot down as surely as was Kennedy. Over the next few days, I was riveted to the T.V., watching Oswald get shot and the president’s funeral, feeling in my bones the sense of despair that seemed to grip the entire country.

I had wanted to go back to Mexico from the moment I had left; the assassination only amped up this feeling of estrangement from my own country. I used Kennedy's murder as ammunition to pressure Ray and my mom to get out of the US again. My naïve point was skewed but my emotions weren't. Instead, they persuaded my grandparents to send money for a bus ticket for me to go to Denver over Christmas vacation.

I was glad to get out of Texas for a couple of weeks and eager to see my grandparents and uncle and his family which now included a new cousin, born after we had gone to Mexico. Curiously, I remember only one day of the entire visit, probably because it was a day that changed everybody's life, at least for a while. Over dinner at my uncle’s house on a Sunday afternoon I garrulously held forth on my adventures in the wild and in Mexico City and explained in minute detail that while Ray was a genius at discovering rich ore-laden mines, he needed investors to transform his finds into reality. My aunt quickly tuned out of the conversation but my uncle listened in rapt attention. He grilled me on the sort of capital needed, the laws, the prospects, on Ray’s ingenuity. By the evening his eyes were dancing.

The next day he had Ray on the phone. My uncle, as it turned out, had been investing in the stock market and had managed to put away a small but substantial nest egg. A friend named Smitty had done the same. Most importantly, both were looking for a new venture, and in my uncle's case, a new adventure. As he had now to support a family, he had become a telephone man and that was not his idea of a life.

Things happened rapidly after that. By the time the Greyhound had pulled into the station in El Paso on my birthday, the 4th of January, my uncle, Smitty and Ray had formed a partnership to exploit the latent load that lurked, at least according to me, under just about every surface of Mexican soil. I don't recall getting much credit, if any at all, for saving Ray from the drudgery of working at the paper, and us from Texas, but it didn't matter a lot to me. Like one of Alger's fine young lads, I took my reward from the fact that something good had happened, and that more good was sure to follow, and that I, in addition to the other members of the family, were going to cash in on it.

In the meantime, I got assigned to help with preparations for the trip that Uncle John and Ray were planning to make in April. Ray acquired a beat up 1954 red Ford pickup, along with a Motors 1954 repair manual, and I was assigned the task of making small repairs on the truck. I quickly made a mess of things, despite the manual, and was instead given the job of building a large locked box to carry goods in the back of the truck. I leapt into this task with zeal, much preferring carpentry over mechanics, and produced in a couple of days a sturdy plywood and pine container, five feet long and three feet wide, complete with an oversized brass padlock assembly, whose hasp extended about one-quarter of the way down the side of the box.

In the evenings I'd sit with Ray and go over the Mexican map with him, plotting the course he and my uncle would take. Ray had decided that as there wasn't sufficient cash to revitalize La Fronteriza, a new mine had to be discovered. The area of interest included most of northern Mexico. I was dying to go with them but knew there would be no way I would be allowed to skip school for a couple of months. Uncle John came toward the end of March and on the first of April the two prospectors set off. I think I believed, up to the moment they actually drove down the street, that some last-minute benediction would be bestowed on me that would put me in the seat between them, but alas it was not to be.

***

Chapter 34: I Become an Accompanist

Perhaps because it was a requirement, I joined the school choir at the beginning of 1964. Despite my musical heritage, I was no singer; but I tried my best, and the director, a tall gangly red-haired fellow named Morrison, was fairly kind: one lousy voice in the alto section, I suppose he reasoned, wouldn't ruin the show. But then, a few weeks after Ray and my uncle had headed off on their grand excursion, the girl who usually played the piano was out sick. Morrison asked if anyone in the chorus could take her place. No one responded. Then, after waiting several seconds for someone else to volunteer, I feebly raised my hand. Morrison eyed me rather skeptically but motioned for me to come forward.

He thrust some sheet music into my hands, then asked, “Can you play this?” It was “Babes in Toyland.”

“I think so,” I said.

“Well, play it then. Class, let Chris run through this. If he can do it, we will continue; if not I'll play it, and Chris, you can rejoin the choir.”

I glanced at the score. It didn't seem difficult, but I hadn't touched the piano in almost a year. I seated myself, arranged the music, stared at the keyboard for a moment, allowed the anxiety to course through my veins, then exit into the still classroom air. I played the first few measures rather slowly, almost tentatively, but by the fifth or sixth bar, everything radically changed. The classroom faded, Morrison disappeared, I picked up the tempo, and it was just me and the piano. And even though I hit a wrong note or two, and even though the music was fairly sappy, I was almost instantly transported beyond myself. My normal brain disengaged from the procedure, was replaced by some unconscious, unbidden force that moved my fingers across the keys, that produced from the back of the instrument glorious sounds. I finished the piece, rested my hands on my lap, and reemerged into reality. No one spoke for a few seconds. Then suddenly behind me I heard applause. Out of the corner of my eye I saw Morrison. He was beaming.

“Very well done,” he said. His ginger eyebrows were arched, as if my performance had taken him by surprise. “Let's do it for real. A little slower, however.”

After class Morrison told me he wished I could be the regular accompanist but that he had committed to Teresa for the year. I told him that was fine, that I really didn't want the job anyway. I went to get my things, but he called me back and began to grill me about my musical education. I gave him an abbreviated version.

“But why aren't you taking lessons now?” he queried, his green eyes staring intently at mine.

“I don't have a piano anymore.”

“Are you going to get one? You've got to get one!” He was wrinkling his forehead and he looked angry.

“I don't think so,” I said. We don't have much money right now.”

“You could rent one. They're not expensive to rent. But you have got to study again.” He looked over at the piano. I was pleased he wasn’t staring at me, at least for a few moments.

“I don't really want to take lessons anymore. It's too much of a hassle”.

He scowled, then burst out, “You're lying!”

I didn't know what to say.

He gazed hard at me, then said, gently now, “Chris, you can practice here every day after 4:00 o'clock if you want, I'll try to coach you, but frankly your talent requires a teacher far more accomplished than I. Do you have music?”

“No,” I said. “I left it in Denver.”

“What do you want to play? I'll get it for you.”

“No, really, that's OK,” I protested. “I don't think I can do this. I mean. Oh, I don't know. I mean….”

He cut me off. “What do you want to play?” he asked again. Now he looked as if he were about to cry, but his voice was resolute.

“How about Satie or Scriabin?” I looked at the floor, then mumbled, “I was working on both when I quit. The Gymnopédies and Scriabin's first sonata. The one in F minor.”

He chuckled, and his face, which had been so drawn, now widened. “You have eccentric tastes, young man. But consider it done. Be here tomorrow at 4:00 o'clock sharp. I’ll probably have to order the scores but I have plenty of music you can begin with. Chopin? Beethoven?"

“Thank you. Either is fine. But do you have Debussy?”

“Debussy it is until the Satie and Scriabin come through.”

I walked home by myself. I wanted to feel happy, but I didn't. I wanted to think that Morrison was handing me an opportunity, and I knew I should be grateful for it, but instead I was in a state of near panic, partly because I couldn't immediately grasp why I was feeling so ambivalent. The half hour at the piano that day, despite the repertoire, had been highly exhilarating. I had, without a doubt, loved it, and I wanted more than anything to continue to play but I was completely afraid of commencing again. I walked along, not really seeing anything or anybody. My hands were sweating; I felt feverish. Some kid I knew from English class hailed me and it took me a moment or so even to respond, so deep was I in my neurotic muddle.

Then, in San Jacinto Plaza, while looking at the alligators in their fenced enclosure, it hit me. My life, I said to myself, wasn't headed in that direction. We were going back to Mexico and Mexico was not equated with pianos. And at the moment we were poor, and I knew that playing just a bit each day on the piano in the music room was not enough either to help me improve or to satisfy me. I couldn't take up Morrison's offer. I couldn't start again and then stop in a few months.

Playing music had been like being on heroin. The high, while doing it regularly was immense, but the withdrawal had been awful. For a long while after I'd quit, every time I'd pass a piano, even in a public place, I would often have a powerful urge to run my fingers over the keyboard. I once found myself in the crowded Focolare cocktail bar in Mexico City, between sets, inching my way toward the instrument, fingers already splayed, my heart beating wildly. Only an extraordinary effort of will had allowed my sense of decorum to prevail over my need. That had been months ago, and until today, I had prided myself on being cured. But I had become intoxicated again, and I feared the outcome of repetitive doses of the piano drug, then addiction, then having to kick again.

All this, while probably not so carefully articulated, had been rattling around in my head as I circuitously made my way home. It was almost dark, the streetlamps on, when I finally started up the hill. Then about halfway up, the apartment visible, I suddenly turned on my heels and began running. I covered the mile or so between the house and the school in short order. Some lights were on in the building, but the main door was locked. I ran around to the side, found a door open, and quietly entered.

My fingers were twitching with anticipation of getting them on the piano keys again. Rhythms and melodies pounded in my forehead as I rapidly ascended the stairs and bounded down the corridor only to come up against the music room's locked door. I knocked on it, though I knew of course, that no one would answer my plea for entrance. Finally, in resignation I slid to the floor, opened my satchel, took out some notepaper, and wrote in haste a letter to Morrison. It said something to the effect that I thanked him for his interest in me, but unfortunately, I would not be able to accept his kindness since I had to be home immediately every day after school to look after my little brother. I didn't reread the note, just slipped it under the door. Then turning away, I slowly walked down the dark corridor, descended the stairs and slid out the door and away from the piano and Satie and Scriabin and another life, and made my way tonelessly into the night.

***

NOTA BENE: The inaugural issue of Wet Cement Magazine has new work by the author. Night Suite, his newest book of poems, will be out later this year from Talisman House.