Klezmorim Between East

and West

Walter Zev Feldman

and West

Walter Zev Feldman

In the late sixteenth century, probably starting in Renaissance Prague and swiftly moving into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazic Jews in Eastern Europe created a professional musicians’ guild known as “klezmer” (pl. klezmorim). Klezmer repertoire was large; as well as dance music, it included improvisations, composed pieces for wedding rituals, and still other pieces for listening. The repertoire also represented a fusion of several elements into a specifically Jewish performance style, including

- the dance music of the European Renaissance,

- the music of the European Baroque,

- modality (nusah) of Ashkenazic prayer, and

- Ottoman music from various social classes.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, as Greco-Ottoman rule receded from both Greater Wallachia (Moldova) and its capital, Iaşi, and from Wallachia and its capital, Bucharest, a fifth element emerged from professional urban music that was rooted in Moldavian folklore. This music was created primarily by the lautar musicians of Roma/Gypsy origin together with local Jewish klezmorim. In Ottoman and then post-Ottoman Moldova, these Jewish and Gypsy musicians worked within a single professional structure.

I am the son of a Yiddish-speaking Jewish immigrant from the shtetl (town) Edinets in Northern Moldova/Bessarabia, a town that had gone from Ottoman to Russian to Romanian rule. Edinets was also a major center of the combined klezmer and lautar/Gypsy music. Having grown up with this music, I also sought out musicians from the local New York Greek and Armenian communities who were often quite familiar with Jewish klezmer music, and who even performed some of it for their Gentile clientele. By my mid-teens I was speaking Turkish, Yiddish, and some Romanian and Russian. In fact, some years later, one of my witty neighbors, an elderly Jewish man from Romanian Moldova, joked about my weak Romanian but rather strong Turkish by composing sentences with a Turkish vocabulary that had dropped out of the Romanian language by the twentieth century. I can still recall him holding the outside door to our apartment house in Manhattan while bowing and uttering the greeting, “Be my guest ” using the Arabic/Ottoman term "misafir" — “Misafir meu…” Clearly, I lived along a continuum from archaic Old World to New.

By the middle 70’s my friend Andy Statman and I approached the leading living exponent of klezmer music—the clarinetist Dave Tarras (1897-1989)—seeking to learn his art. From an old klezmer lineage in Podolian Ukraine, Tarras had slipped across the border at the time of the Russian civil war, and learned even more music from the klezmer and lautar musicians in Edinets. For many decades in New York he continued to compose and record new melodies in the Bessarabian klezmer style. After a couple of years of study, Andy and I approached Ethel Raim at the Balkan Arts Center (now the Center for Traditional Music and Dance), and we crafted a proposal to the NEA to study with, record and present Tarras on stage. The resulting concert—in November 1978—was the first public appearance of my English neologism “Jewish Klezmer Music,” and was an overwhelming success. Both the term and the music quickly gained popularity, first among Jews in America, then in Germany, and soon world-wide.

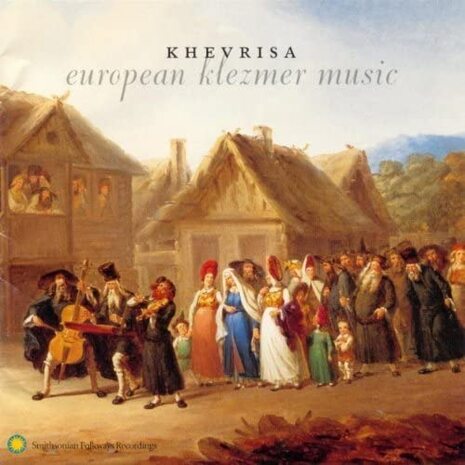

Ten years after Tarras’ death I interviewed the potentially last living klezmer band leader trained in Eastern Europe prior to WWII—the violinist Yermye Hescheles (1910-2010), from the region of Lvov in Austrian Eastern Galicia. Hescheles was also a major poet in the Yiddish language. Conducted in his apartment near West 14th Street, our vivid exchanges inspired my recreation of an older klezmer ensemble, which we called “Khevrisa.” Khevrisa featured Steven Greenman (from Cleveland) as first fiddle, Michael Alpert (New York and LA) on second fiddle, myself on tsimbl (cimbalom) and Stuart Brotman (San Francisco) on bass. We were joined at times by Alicia Svigals (NYC) on second fiddle as well. Hescheles’ advice on some of our early playing of this repertoire was priceless. In essence Khevrisa was a klezmer ensemble long current in his native Galicia and elsewhere that had not changed its composition since the early eighteenth century.a

|

In 1999 we recorded a CD, which would be issued by Smithsonian Folkways as “European Klezmer Music.” As part of our “Moldavian Klezmer Suite,” we performed a piece that had been played by the klezmer fiddler Avrom Buchici (1883-1968), and recorded in Bughici’s home in Iaşi in the late ‘60s by the noted Romanian Jewish historian Itsik Svarts. To perform it Steven tuned his violin “a la turca,” so that he could produce octave drones on his A string tuned down to E, in Yiddish called the “two-strings” (tsvey shtrunes) tuning. The musical genre was generally called simply terkisher

(“Turkish”), and it was used as part of a wedding ritual or concert, rather than as dance music. Its rhythm, however, was clearly derived from the Greek dance syrto, a fact already documented in 1751 by Charles Fonton, French interpreter for the Ottoman’s Sublime Porte, and known as “Danse Greque.” The compositional structure of Bughici’s terkisher was most closely related to the instrumental peşrev genre of the |

Janissary Band [1] (mehter) [2] Its mode was on the border between Ashkenazic prayer and Ottoman Classical Music[3] , in particular the makam (mode) Nikriz. Though it took many years before I could come up with an adequate explanation of what this genre and performance had really meant both to the Jews and Gentiles in several countries, I continue to admire the piece. (See 18 Bughici's Terkisher Freylakhs.)

Tracing the origin of this “two-strings” violin tuning adds another ingredient to the plot. In the mid-eighteenth century, led by Greek and Moldavian fiddlers in Iaşi, the Ottomans had just adopted the European violin in the form of the viola d’amore, a Baroque violin. These musicians created a synthesis of a Baroque and a Perso-Turkic bowed instrument’s timbre and tuning; and, by the end of the eighteenth century the leading performer of this instrument at the Ottoman court was the Moldavian Kemani Miron. Between 1795 and 1806 he was the most highly paid musician at the Court, and even in 1834 he was referred to in Court records as “the venerable violinist Miron.”

By the time of Miron’s generation, klezmer violinists and cimbalists were already quite prominent in Iaşi, and some played in the highest social circles. Thanks to further research by Itsik Svarts, we know that klezmorim and Gypsy lautari had been travelling yearly from Moldova to Istanbul since the later eighteenth century. The letters they had sent back home to their wives were preserved in the synagogue of the klezmer guild in Iaşi, still in existence today. However, Miron was not a composer, so we can only wonder what of the various elements of playing might have influenced his own work, and whether his synthesis of Turkish, urban Greek and klezmer musical styles might have filtered back to Moldova.

Thus, in that one elegant terkisher , first recorded in the 1960s in Bughici’s Iaşi home, and then by Khevrisa in New York in 1999, you can hear the musical conversations among Ottoman Turks, Ashkenazic Jews, Poles, Moldavians and Greeks that have persisted over at least three centuries. Pondering these musical interactions, you are forced to let go of many preconceptions about the nature of the “East” and the “West,” and their human interactions on European soil. Not least of these preconceptions is in regard to the culture of the Yiddish-speaking Jews. Along with their many connections with the music, dance and folk literature of early modern Germany—broadly speaking—we can find links with both the music and folk literature of the Ottoman Turks. Recently, research into the genesis of the Hasidic movement by Moshe Idel in Jerusalem also points to their fruitful interactions with Turkish and Tatar Sufis and shamans along the Ottoman/Polish borderlands of Moldova and Podolian Ukraine.

Preceding Bughici’s terkisher, we included a violin solo that Steven played, named terkisher gebet or “the Turkish Prayer.” Intriguingly, this rubato melody (without a fixed meter) ended with a very distinctive formula that also appeared prominently in the piece performed (but not composed) by Bughici. We learned the Turkish Prayer from a Moldavian fiddler in New York named Leon Schwartz (1901-1990), who had in turn learned it from the Galician klezmer musician, Julius Spielman. At the turn of the twentieth century, Spielman had traveled from his native Galicia to Istanbul. In an instance of sheer serendipity I had come across a description of some of these klezmer musicians of two generations earlier, in the travelogue of the English writer Julie Pardoe. In her book The Beauties of the Bosphorus from 1839, while speaking of the meadow known as the Sweet Waters of Asia (Küçük Su Kasri), near the Anadolu Hisari castle, she writes:

By the time of Miron’s generation, klezmer violinists and cimbalists were already quite prominent in Iaşi, and some played in the highest social circles. Thanks to further research by Itsik Svarts, we know that klezmorim and Gypsy lautari had been travelling yearly from Moldova to Istanbul since the later eighteenth century. The letters they had sent back home to their wives were preserved in the synagogue of the klezmer guild in Iaşi, still in existence today. However, Miron was not a composer, so we can only wonder what of the various elements of playing might have influenced his own work, and whether his synthesis of Turkish, urban Greek and klezmer musical styles might have filtered back to Moldova.

Thus, in that one elegant terkisher , first recorded in the 1960s in Bughici’s Iaşi home, and then by Khevrisa in New York in 1999, you can hear the musical conversations among Ottoman Turks, Ashkenazic Jews, Poles, Moldavians and Greeks that have persisted over at least three centuries. Pondering these musical interactions, you are forced to let go of many preconceptions about the nature of the “East” and the “West,” and their human interactions on European soil. Not least of these preconceptions is in regard to the culture of the Yiddish-speaking Jews. Along with their many connections with the music, dance and folk literature of early modern Germany—broadly speaking—we can find links with both the music and folk literature of the Ottoman Turks. Recently, research into the genesis of the Hasidic movement by Moshe Idel in Jerusalem also points to their fruitful interactions with Turkish and Tatar Sufis and shamans along the Ottoman/Polish borderlands of Moldova and Podolian Ukraine.

Preceding Bughici’s terkisher, we included a violin solo that Steven played, named terkisher gebet or “the Turkish Prayer.” Intriguingly, this rubato melody (without a fixed meter) ended with a very distinctive formula that also appeared prominently in the piece performed (but not composed) by Bughici. We learned the Turkish Prayer from a Moldavian fiddler in New York named Leon Schwartz (1901-1990), who had in turn learned it from the Galician klezmer musician, Julius Spielman. At the turn of the twentieth century, Spielman had traveled from his native Galicia to Istanbul. In an instance of sheer serendipity I had come across a description of some of these klezmer musicians of two generations earlier, in the travelogue of the English writer Julie Pardoe. In her book The Beauties of the Bosphorus from 1839, while speaking of the meadow known as the Sweet Waters of Asia (Küçük Su Kasri), near the Anadolu Hisari castle, she writes:

|

All ranks alike frequent this sweet and balmy spot. Wallachian and Jewish musicians are common… But these oriental troubadours are not without their rivals in the admiration of the veiled beauties who surround them; conjurors, improvisatori, story-tellers, and Bulgarian dancers are there also, to seduce away a portion of their audience, while interruptions caused by fruit, sherbet and water-vendors are incessant. They are, however, the most popular of all, and a musician whose talent is known and acknowledged seldom fails to spend a very profitable day at the Asian sweet waters.

|

Both the Turks and the Greeks of Istanbul appreciated this music, and by the late nineteenth century some of the leading Turkish musicians were imitating this mixed klezmer/lautar style in popular dance forms known as longa and sirto. Several documents and recordings from this movement survive from the years just prior to World War I. These include a couple of ’78 recordings by Moldavian klezmer bands issued in Istanbul with labels in Greek, as well as an intriguing “double,” a klezmer fiddle recording made in Lwow by a certain Josef Solinski and a popular dance composition called “Nihavent sirto” by Kevser Hanım [4], a leading female violinist in Istanbul who taught at the Darülelhan Conservatory between 1917 and 1927. Both the klezmer and the Turkish pieces are closely connected—the Kevser dance tune seems like a simplified version of Solinski’s composition—and both appeared circa 1912. Many klezmorim and lautari in Moldova performed Solinski’s melody well into the late twentieth century. Kevser Hanım’s piece—now termed “Nihavent Longa”—is still part of the nightclub music of Istanbul. But beyond the scholarly record, dare we surmise that these two violinists had actually met somewhere in Istanbul? In a nightclub in Pera, or at the Sweet Waters of Asia meadow? (See Rum Fantasi 3 and Nihavent Longa)

Over the next several years, as I researched both Ottoman music and Ashkenazic klezmer music, the historical, sociological and musical aspects of the intersection of these two very different cultures gradually became clearer. Between 2011 and 2015 I received funding from New York University in Abu Dhabi to conduct field work in the Republic of Moldova, working both with lautari (indeed in our old shtetl Edinets) and with musicologists in Chişinau. Additionally I conducted research—aided by my friend and then-assistant Christina Crowder—with lautari and Jewish musicians as far afield as Germany, Israel and Canada. Among many other facts, I learned that Yiddish became the professional language of the lautari “Gypsy" professional musicians in those northern Moldavian towns whose population was then predominantly Jewish. In the past, Greek and probably Turkish had also been part of the linguistic knowledge of many local Ashkenazic Jews.

Most recently I was privileged to have a fellowship in Advanced Jewish Studies at Oxford University to pursue this Ottoman/klezmer connection further from the perspective of Ottoman history. In fact, the social conditions that produced this music were already disappearing when Bughici was growing up in early twentieth-century Iaşi. Thus, I needed a deeper historical overview…

In the seventeenth and especially in the early eighteenth century, as Ashkenazic Jews settled in Ottoman-ruled Moldova, a kind of Ottoman musical koine was created in the North of Eastern Europe. While some of this repertoire was restricted to internal use by Ashkenazic Jewish communities, other examples evidently were performed for the local aristocracies. Several European states sent for outdoor mehter ensembles from the Ottoman realm to attend their courts and to come to their capital cities. In the early 18th century—and early among his peers in doing so—the Polish King Augustus II requested the services of such a band. A “crossover” of this phenomenon was the appearance of Jewish klezmer musicians from the Prague ghetto to play “Turkish music” at the court of the Habsburg Emperor Leopold II. Quite possibly, a direct line runs from Ottoman mehter dance music, through the Ottomanized klezmer performance, to Mozart’s Turkish rondo of 1783. An Ottomanized klezmer violin repertoire—mainly based on the peşrev--was notated in the same years in the manuscript of the cantor (khazzan), Aaron Beer, in Berlin. Cantor Beer even composed a shorter piece (no. 404) in an older prototype of what would later be called the terkisher genre.

Lwow, later the home city of Hescheles, was both the emporium for goods coming from the Black Sea and the land-route through Ottoman Moldova. The city was known for its prosperous Greek and Armenian quarters; and its popular music in the 17th century revealed a dichotomy between Ottoman-flavored performances led by the “sirbska” fiddles and the small cimbalom, and the “Italian” music with violin and harpsichord. In 1673 aristocratic entertainment with Jewish, Karaite, [5] Gypsy and Turkish dancers and dancing troupes traveled even as far north as Warsaw. These performances probably were also connected in some fashion to a dominant “Sarmatian Theory” of Polish aristocratic origins which claimed that the Polish aristocracy—in contradistinction to the Polish people—were a conquering Oriental race originating with the ancient Sarmatians from North of the Black and Caspian Seas. Indeed, the Polish aristocracy often imitated many aspects of the dress and culture of the neighboring Crimean Tatars. Moreover the Polish-Ottoman border was quite porous; numerous Polish-Lithuanian subjects sought their fortunes in the rather more “democratic” Ottoman territories, sometimes entering the Ottoman service, as documented recently by Professor Dariusz Kolodjejczyk of the University of Warsaw. Not infrequently, cases of kidnapping by Tatar slave-raiders occurred. A classic example of Tatar kidnapping was that of Wojciech Bobowski (ca. 1610-1675) from Lwow, who converted to Islam under the name Ali Ufki (or Ufuki) Bey, and became first an Ottoman court musician—a cimbalist—and then an interpreter.[iv]

In this centuries-long saga the musical actors were mainly Ashkenazic Jews, Moldavians, Roma, Greeks and Turks, who all found the musical, cultural and linguistic means to communicate, to share and to create together. By the mid-twentieth century, however, demographic and social realities changed to the point that these intercommunal and interreligious contacts had become almost unimaginable. Rare recordings and manuscript notations allow us a glimpse of what these creations were—and, moreover, to enjoy their unexpected beauty.

N.B.: I would like to thank Irina Bughici Graziani of Jerusalem for sharing memories of her grandfather Avrom Bughici.

NOTES:

[1] The Janissaries were the elite palace guard for the Ottoman sultans. Members were often the sons of conquered Christian peoples in the Balkan parts of the Ottoman Empire, taken in a system called Devshirme, made to embrace Islam, but then given quite a lot of respect and privilege.

[2] See Mehmet Ali Sanlıkol, The Musician Mehters. Istanbul: Isis, 2012. The official mehter ensembles had both a military and important ceremonial/symbolic functions throughout the Ottoman Empire.

[3] “Art music” is a literal translation of sanat müziği but the standard translation is Ottoman Classical Music.

[4] “Hanım” is a honorific, loosely translated as “lady” but more like the Spanish Doña. Little is known about her, including her surname.

[5] Karaism is an ancient sect within Judaism. Karaites in the Middle East appear to be of ethnic Jewish origin. However, Karaities in historical Poland/Lithuania appear to be Kuman Turks who converted to sectarian Judaism after the fall of the Khazarian Empire. They continued to speak Kumanic and preserved many Turkic folk customs into the earlier 20th century.

Most recently I was privileged to have a fellowship in Advanced Jewish Studies at Oxford University to pursue this Ottoman/klezmer connection further from the perspective of Ottoman history. In fact, the social conditions that produced this music were already disappearing when Bughici was growing up in early twentieth-century Iaşi. Thus, I needed a deeper historical overview…

In the seventeenth and especially in the early eighteenth century, as Ashkenazic Jews settled in Ottoman-ruled Moldova, a kind of Ottoman musical koine was created in the North of Eastern Europe. While some of this repertoire was restricted to internal use by Ashkenazic Jewish communities, other examples evidently were performed for the local aristocracies. Several European states sent for outdoor mehter ensembles from the Ottoman realm to attend their courts and to come to their capital cities. In the early 18th century—and early among his peers in doing so—the Polish King Augustus II requested the services of such a band. A “crossover” of this phenomenon was the appearance of Jewish klezmer musicians from the Prague ghetto to play “Turkish music” at the court of the Habsburg Emperor Leopold II. Quite possibly, a direct line runs from Ottoman mehter dance music, through the Ottomanized klezmer performance, to Mozart’s Turkish rondo of 1783. An Ottomanized klezmer violin repertoire—mainly based on the peşrev--was notated in the same years in the manuscript of the cantor (khazzan), Aaron Beer, in Berlin. Cantor Beer even composed a shorter piece (no. 404) in an older prototype of what would later be called the terkisher genre.

Lwow, later the home city of Hescheles, was both the emporium for goods coming from the Black Sea and the land-route through Ottoman Moldova. The city was known for its prosperous Greek and Armenian quarters; and its popular music in the 17th century revealed a dichotomy between Ottoman-flavored performances led by the “sirbska” fiddles and the small cimbalom, and the “Italian” music with violin and harpsichord. In 1673 aristocratic entertainment with Jewish, Karaite, [5] Gypsy and Turkish dancers and dancing troupes traveled even as far north as Warsaw. These performances probably were also connected in some fashion to a dominant “Sarmatian Theory” of Polish aristocratic origins which claimed that the Polish aristocracy—in contradistinction to the Polish people—were a conquering Oriental race originating with the ancient Sarmatians from North of the Black and Caspian Seas. Indeed, the Polish aristocracy often imitated many aspects of the dress and culture of the neighboring Crimean Tatars. Moreover the Polish-Ottoman border was quite porous; numerous Polish-Lithuanian subjects sought their fortunes in the rather more “democratic” Ottoman territories, sometimes entering the Ottoman service, as documented recently by Professor Dariusz Kolodjejczyk of the University of Warsaw. Not infrequently, cases of kidnapping by Tatar slave-raiders occurred. A classic example of Tatar kidnapping was that of Wojciech Bobowski (ca. 1610-1675) from Lwow, who converted to Islam under the name Ali Ufki (or Ufuki) Bey, and became first an Ottoman court musician—a cimbalist—and then an interpreter.[iv]

In this centuries-long saga the musical actors were mainly Ashkenazic Jews, Moldavians, Roma, Greeks and Turks, who all found the musical, cultural and linguistic means to communicate, to share and to create together. By the mid-twentieth century, however, demographic and social realities changed to the point that these intercommunal and interreligious contacts had become almost unimaginable. Rare recordings and manuscript notations allow us a glimpse of what these creations were—and, moreover, to enjoy their unexpected beauty.

N.B.: I would like to thank Irina Bughici Graziani of Jerusalem for sharing memories of her grandfather Avrom Bughici.

NOTES:

[1] The Janissaries were the elite palace guard for the Ottoman sultans. Members were often the sons of conquered Christian peoples in the Balkan parts of the Ottoman Empire, taken in a system called Devshirme, made to embrace Islam, but then given quite a lot of respect and privilege.

[2] See Mehmet Ali Sanlıkol, The Musician Mehters. Istanbul: Isis, 2012. The official mehter ensembles had both a military and important ceremonial/symbolic functions throughout the Ottoman Empire.

[3] “Art music” is a literal translation of sanat müziği but the standard translation is Ottoman Classical Music.

[4] “Hanım” is a honorific, loosely translated as “lady” but more like the Spanish Doña. Little is known about her, including her surname.

[5] Karaism is an ancient sect within Judaism. Karaites in the Middle East appear to be of ethnic Jewish origin. However, Karaities in historical Poland/Lithuania appear to be Kuman Turks who converted to sectarian Judaism after the fall of the Khazarian Empire. They continued to speak Kumanic and preserved many Turkic folk customs into the earlier 20th century.

Further Reading:

Walter Zev Feldman, “Klezmer Revived: Dave Tarras Plays Again” in Ilana Abramovitch and Sean Galvin (eds.), Jews of Brooklyn. Brandeis University Press (2000).

Walter Feldman, “Klezmer Tunes for the Christian Bride,” Revista de Etnografii şi Folclor (Bucharest, 2020: 5-35) The author notes this more scholarly article in connection with Kevser Hanim and music still heard in clubs in Istanbul.

Walter Zev Feldman, Klezmer: Music, History and Memory (Oxford U Press, 2016: 200).

Paul Nettl, Alte jüdische Spielleute und Musiker. (Prague: J. Fleisch, 1923). Re: Jewish musicians from the Prague ghetto play for Hapsburg King Leopold II.

Abraham Zevi Idelsohn, Thesaurus of Hebrew-Oriental Melodies. Vol. 6: The Synagogue Song of the German Jews in the 18th Century. (Leipzig: Friederich Hofmeister, 1932: 144).

Judith Haug, Ottoman and European Music in ‘Ali Ufuki’s Compendium, MS Turc 292: Analysis, Interpretation, Cultural Context: Monograph. R.eihe XXVI (Schriften zur Musikwissenschaften aus Münster, Band 25, 2019).

Walter Zev Feldman, “Klezmer Revived: Dave Tarras Plays Again” in Ilana Abramovitch and Sean Galvin (eds.), Jews of Brooklyn. Brandeis University Press (2000).

Walter Feldman, “Klezmer Tunes for the Christian Bride,” Revista de Etnografii şi Folclor (Bucharest, 2020: 5-35) The author notes this more scholarly article in connection with Kevser Hanim and music still heard in clubs in Istanbul.

Walter Zev Feldman, Klezmer: Music, History and Memory (Oxford U Press, 2016: 200).

Paul Nettl, Alte jüdische Spielleute und Musiker. (Prague: J. Fleisch, 1923). Re: Jewish musicians from the Prague ghetto play for Hapsburg King Leopold II.

Abraham Zevi Idelsohn, Thesaurus of Hebrew-Oriental Melodies. Vol. 6: The Synagogue Song of the German Jews in the 18th Century. (Leipzig: Friederich Hofmeister, 1932: 144).

Judith Haug, Ottoman and European Music in ‘Ali Ufuki’s Compendium, MS Turc 292: Analysis, Interpretation, Cultural Context: Monograph. R.eihe XXVI (Schriften zur Musikwissenschaften aus Münster, Band 25, 2019).

Feldman's most recent work is From Rumi to the Whirling Dervishes; Music,Poetry, and Mysticism in the Ottoman Empire, puboished by Edinburgh University Press, Junaury 2022.